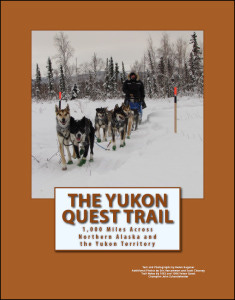

This excerpt is an edited version of the first chapter of The Yukon Quest Trail, : 1,000 Miles Across Northern Alaska and the Yukon Territory, by Helen Hegener, published in 2014 by Northern Light Media. The Yukon Quest Trail takes readers checkpoint by checkpoint from Fairbanks to Whitehorse, an extraordinary journey in which the author shares insights and details of the trail, along with the incredible history of both the race and the wild and beautiful land it crosses. Over 180 full-color photographs by the author and by photographers Eric Vercammen and Scott Chesney provide an unparalleled look at the trail, the mushers, the dogs and more. Also included are Trail Notes for Mushers, detailing the route in both directions, compiled by two-time Yukon Quest Champion John Schandelmeier.

The Yukon Quest Trail, : 1,000 Miles Across Northern Alaska and the Yukon Territory, by Helen Hegener, 151 pages, 8.5″ x 11″ full color format, bibliography, maps, indexed. $29.00, plus $5.00 for First Class shipping.

Chapter One

An event like the 1,000 mile Yukon Quest generates stories and legends with almost every running, but the first race, the inaugural Yukon Quest, stands alone as the epic adventure which started it all.

On the Yukon Quest website, www.yukonquest.com, there’s a somewhat abbreviated version of the history of the race, reprinted here almost in its entirety:

“In 1983, four mushers sat at a table in the Bull's Eye Saloon in Fairbanks, Alaska. The conversation turned to a discussion about a new sled dog race and "what-ifs."

• What if the race followed a historical trail?

• What if it were an international sled dog race?

• What if the race went a little longer?

• What if it even went up the Yukon River?

As early as 1976, a Fairbanks to Whitehorse sled dog race had been talked of. But it wasn't until this conversation between Roger Williams, Leroy Shank, Ron Rosser and William "Willy" Lipps that the Yukon Quest became more than an idea. The mushers named the race the "Yukon Quest" to commemorate the Yukon River, which was the historical highway of the north. The trail would trace the routes that the prospectors followed to reach the Klondike during the 1898 Gold Rush and from there to the Alaskan interior for subsequent gold rushes in the early years of the 1900s.”

A somewhat longer version of the history appears in the photo-rich book by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Martin, titled Yukon Quest Sled Dog Race, published in 2013 by Arcadia Publishing. In her book Elizabeth Martin recounts a little more detail about the race’s colorful beginnings:

“The Yukon Quest International Sled Dog Race was born when LeRoy Shank and Roger D. Williams, along with Shank’s wife, Kathleen, and some friends, got the idea for a different kind of race after running the Bull’s Eye-Angel Creek 125, a 125-mile race between Bull’s Eye Saloon and Angel Creek Lodge. After tossing around the idea for about three weeks, Shank decided to contact someone in Whitehorse to see if the race were possible. He called the chamber of commerce and was eventually connected with Lorrina Mitchell, who became a Yukon-based board member. She was good friends with Wendy Waters, who also joined the original Yukon board. Waters and Mitchell took care of the Whitehorse/Canada end, and a race was born.”

Lorrina Mitchell had begun racing when only 16; already a veteran of sprint and mid-distance races, she signed up to run her team in the first Yukon Quest. Mary Shields was the only other woman musher in the first race. LeRoy Shank had posters made which described the rudiments and purposes of the race:

Yukon Quest Sled Dog Race

1,000 Miles Over the Gold Rush Trail

Fairbanks to Whitehorse • February 25, 1984

$15,000 in Gold - First Place

Standard long distance rules with a few notable exceptions as follows:

1. Twelve dogs starting maximum, eight dogs starting minimum.

2. Three dogs drop limit.

3. Same sled or toboggan, start to finish.

4. Mandatory 36-hour layover at Dawson.

The purposes for which this corporation was organized are:

To support long distance sled dog racing and in particular to support a sled dog race of international character between Fairbanks, Alaska and Whitehorse, Yukon Territory.

To provide an opportunity for and encourage participation in an epic by musher and dog, without regard to the musher’s sex, race, religion, national origin, background, age, vocation, or economic standing.

To recognize and promote the spirit that compels one to live in the Great North Land, an international spirit that knows no governmental boundaries, to bring public attention to the historic role of the Arctic Trail in the development of the North Country, and the people and animals that strove to meet its challenge.

To commemorate the historic dependence on man on his sled dogs for mutual survival in the Arctic Environment and to perpetuate mankind’s concern for his canine companion’s continued health, welfare, and development.

To encourage and facilitate knowledge and application of the widest variety of bush skills and practices that form the foundation of Arctic Survival.

To offer an experience that reflects the spirit and perseverance of the pioneers who discovered themselves in their wild search for adventure, glory, and wealth in the Frozen North.

Elizabeth Martin continued: “To get sponsors and mushers, LeRoy Shank put flyers and posters all over Fairbanks and North Pole and sent them to anyone he thought might support a Fairbanks-based long distance race, a different kind of event in which skill and know-how mattered more than money and sponsorships. It would feature the musher and the dogs on their own, with only their wits, survival skills, and gear between them and disaster, like it was 100 years ago. After a few spots on a local radio show and columns by Fairbanks Daily News-Miner sports writer Bob Eley, interest was sparked.”

People often compare the Yukon Quest to the only other 1,000-mile sled dog race, the Iditarod. The differences between the two races were neatly summed up by Adam Killick in his book, Racing the White Silence (Penguin Books, 2002): “...Where the Iditarod has twenty-three checkpoints over its course, the Quest has only eight. The Quest crosses four mountain passes—all of which are steeper than the sole pass on the Iditarod—and cuts through the cold, dry heart of the Yukon and Alaska. It is run several weeks earlier than the Iditarod, beginning in early February, farther from the sun in the Earth’s axial tilt. Mushers are on their own in the Quest, with the exception of one thirty-six-hour mandatory layover in Dawson City, the halfway point, where handlers can step in and provide primary care for the dogs. You are allowed only one sled: if it happens to be damaged by a rampaging moose, which happens to a musher every few years or so, it means wandering into the woods to look for replacement parts.”

Mushers were advised to have a large sled, as the mandatory equipment requirements included a cold weather sleeping bag, an ax, a pair of snowshoes, a map and compass, eight booties for each dog, Yukon Quest promotional materials, and three pounds of food for each dog for every 50 miles of the race. Optional equipment included additional boots and cold weather clothing, a cookstove, dog dishes, headlamp, thermos, face mask, first aid kit, sewing kit, tent, tarp, repair kit, flashlight, batteries and more.

The morning of the first Yukon Quest, February 25, 1984, dawned clear and cold and saw twenty- six teams gathered for the inaugural start in Fairbanks. It was minus twenty degrees below zero, but the temperature was falling steadily, and by that night the teams on the trail would be facing forty below.

David “Pecos” Humphrey, from Talkeetna, was the first musher off the starting line with a dozen dogs; he was followed, in order, by Sonny Lindner with 9 dogs, Bill Cotter (10), Joe Runyan (12), Jeff King (11), Bruce Johnson (11), Nick Ericson (10), Mary Shields (10), Bob English (9), Gerald Riley (12), Jack G. Stevens (12), Harry Sutherland (10), Jack Hayden (10), Frank Turner (10), Dan Glassburn (11), David Klumb (10), Lorrina Mitchell (8), Chris Whaley (12), Ron Aldrich (12), John Two Rivers (12), Shirley Liss (8), Darryle Adkins (10), Murray Clayton (11), Wilson Sam (12), Senley Yuill (10), and Kevin Turnbough (11). Only six would scratch before Whitehorse.

In Yukon Quest Sled Dog Race, Elizabeth Martin described the first crossing of Eagle Summit, a name which still elicits a pause for most mushers facing the trail: “Eagle Summit.... is a 3,952-foot gap through the White Mountains of Central Alaska. An early explorer, Hudson Stuck, wrote in 1916: ‘The Eagle Summit is one of the most difficult summits in Alaska. The wind blows so fiercely that sometimes for days together its passage is almost impossible.’

“In 1984, Mother Nature threw a howling blizzard out just to shake things up. Ice formed around the dogs’ and mushers’ faces, so they could not see. The wind keened, piercing even the warmest furs and parkas, and got into their heads like a banshee on the prowl. Several mushers were no match for the wind, which was strong enough to knock down even the biggest mushers and their 300-pound sleds. Most mushers struggled through, but a few turned back to camp at the base in order to wait for better conditions. Both sleds and dogs took a beating, but no major injuries occurred. ‘I was scared,’ Bob English admitted. ‘The dogs were scared.’”

The teams descended Eagle Summit into Circle Hot Springs, where the temperature dropped to minus fifty degrees and icy coats formed on the dogs and mushers alike as the humid warm air met the frigid cold. The teams raced on, across wide Medicine Lake and along the twisting Birch Creek and down onto the wide Yukon River at Circle City, then upriver 49 miles to Eagle, and another 95 miles through the jumble ice, around dangerous open leads of water, across the Canadian border and finally into historic Dawson City for a well-earned rest.

Leaving Dawson City after a 36-hour layover, the teams climbed over 4,049’ King Solomon's Dome, the weathered peak that some locals still believe conceals the legendary mother lode of the 1898 Klondike gold rush. Down through the Black Hills to the Pelly River and then across a big broad country to meet the Yukon River again near the Carmacks checkpoint, 170-some miles from Whitehorse. The Whitehorse Daily Star would later say of the first race, “From the time the Quest started in late February to its finish in March, dog mushers battled blizzards, tough terrain, cold and warm temperatures. Many of them found the first Quest a quest to survive.”

Frontrunners Sonny Lindner and Joe Runyan pushed toward the Whitehorse finish line. Joe had been the first musher to leave Dawson City, but in that position he was breaking trail for all of the teams behind him, and once Sonny passed him in the Black Hills he never gave up the lead.

Trail conditions were so unseasonably warm that the trail became too soft for the teams, there was no snow in some places, and race marshal Carl Huntington and the other race officials began considering options. Elizabeth Martin titled her chapter at this point ‘Hazards Mounting to the End of the Line,’ and explained, “For safety reasons, officials decided to truck the teams from Carmacks to Fox Lake, bypassing about 13 miles of snowless, rocky trail and the hazardous Klondike Highway.”

Hundreds of excited fans lined First Avenue in Whitehorse for the historic finish of the first Yukon Quest. Sonny Lindner’s team crossed the finish line at 1:20 p.m., March 8, 1984, for an official time of twelve days and five minutes. Harry Sutherland was five hours and ten minutes behind him for second place; Bill Cotter was third, and Joe Runyan, who had led for much of the race, was fourth. Jeff King, who would later become an Iditarod legend, came in fifth.

The 1984 inaugural Yukon Quest was an unqualified success, and the race has since become a much-anticipated annual event for mushing fans the world over. It has earned the distinction of being the “Toughest Sled Dog Race in the World,” and for the intrepid mushers who take on the challenge, the Yukon Quest lives up to its reputation.

“In this era of space shuttles and supersonic jets carrying people around the globe in a matter of hours, or satellite communications sending messages across continents in seconds, we tend to forget exactly how far 1,000 miles really is and what kind of an effort is required to travel it.”

—John Firth, Fulda Yukon Quest (Societats-Verlag 1997)