In 1935 the U.S. Government transported 200 families from the Great Depression-stricken midwest to a valley of unparalleled beauty in Alaska, where they were given the chance to begin new lives in a federally-funded social experiment, part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal for America. “A Mighty Nice Place,” The History of the 1935 Matanuska Colony Project, by Helen Hegener, was published by Northern Light Media in July, 2016. This history of the Matanuska Valley is excerpted from the second chapter of the book.

A History of the Land

by Helen Hegener

In Exploration of Alaska 1865-1900 (University of Alaska Press, 1992), Morgan B. Sherwood notes, “An early mention of the agricultural value of the Matanuska Valley appeared in Glenn’s report.”

The “Glenn’s report” referred to was that of Captain Edwin Forbes Glenn, the U. S. Army officer in charge of explorations in south-central Alaska in 1898 and 1899. Captain Glenn’s descriptions of his expedition are a fascinating look at the earliest official incursions into the Cook Inlet and Matanuska regions:

“We rounded Cape Elizabeth in the early morning of May 31, and consumed the remainder of the day and until nearly midnight in reaching Tyoonok, at which place we found scattered along the beach from 200 to 500 prospectors, about 100 Indians (men women and children) and the trading station of the Alaska Commercial Company. This place is generally considered to be the head of navigation in Cooks Inlet, but I subsequently ascertained that excellent anchorage, plenty of water, and a safe harbor, were obtainable at Fire Island, which is situated between the mouths of Turnagain Arm and Knik Inlet, a distance of about 18 miles farther up the inlet.”

“On this date (June 1), having discharged Guide Howe, I secured as guide Mr. H. H. Hicks, who had been for three years prospecting up the Matanuska River, with which country and the Indians located on or near the same he was very familiar, having traded with them during his entire residence in Alaska.”

“The five animals sent me having had sufficient rest, and believing, from the best information obtainable, that an outlet into the interior could be found via the Matanuska River, I decided to send Lieut. J. C. Castner, U. S. A., with Mr. Hicks as guide and a sufficient number of enlisted men, up this stream for the purpose of cutting a trail as far as practicable before the mules needed and called for arrived.”

“We reached Knik Inlet finally, cast anchor, and waited for the vessel to go aground before attempting to unload. We were deeply impressed with the appearance of everything in this inlet. The weather was much more mild than in the lower part of the inlet, and the season more advanced than at Tyoonok or at Ladds Station by at least three weeks. The trees were in almost full leaf, and the grass a sort of jointed grass resembling the famous blue grass of Kentucky was abundant and at least a foot high. The length of this arm is about 25 miles. Coming in at the head of it were the Matanuska and Knik rivers, the former from the east, the latter from the south. The valley there is quite flat and about 20 miles across. In fact, the valleys of both streams are in full view from just above the trading station.

“This inlet, when the tide goes out, seems to be an immense mud flat. I learned from reliable sources that about two years ago the navigable channel of this inlet passed directly in front of and close to the trading station. But it seems that at that time an immense body of water came down, apparently from the Knik River, destroying not only the trading establishment of the Alaska Commercial Company, located on the opposite bank of the inlet, but also a number of Indian houses. The Indians say that as this flood came down it presented a solid wall of water at least 100 feet high. This statement, however, should be very much discounted. At any rate, the effect, in addition to the destruction of the houses, was to leave deposited in front of the present trading company’s establishment an immense amount of mud and sand that extends out from the shore for nearly if not quite half a mile, and prevented us from landing at the station. We were forced to cast anchor at the mouth of the small stream, 2 miles below, that is used by the Knik Indians during the fishing season.”

The “immense body of water” referred to by Captain Glenn was well-documented as a significant event in the Valley’s history. In Shem Pete’s Alaska: The Territory of the Upper Cook Inlet Dena’ina (University of Alaska Press-Fairbanks, 1987), the flooding is mentioned:

“Just before 1900, three Indian villages along the Knik River were destroyed by a great flood, which was believed to be the result of the breakout of Lake George. No previous flood damage along the Knik River had been recorded, although the lake emptied once every 15 to 20 years according to Indians living in the area.”

Lake George, a glacial lake formed near the face of the Knik glacier, received national recognition by the National Natural Landmark Program because of a unique natural phenomenon called a “jökulhlaup“, an Icelandic term for glacial lake outburst flood. The intermittent breakup of the lake’s ice dam would send a violent wall of water, ice and debris down the river valley causing massive flooding and sometimes devastation to local settlers’ properties. The Lake George jökulhlaup has not occurred since 1967, due in part to glacial recession, but also for reasons associated with the massive Good Friday Earthquake of 1964.

W. C. Mendenhall, a member of Captain Glenn’s expedition, made the first rough geological survey of the Matanuska Valley. According to the 1912 U.S. Geological Survey bulletin, Geology and Coal Fields of the Lower Matanuska Valley, Alaska, by George Curtis Martin and Frank James Katz:

“The Matanuska Valley was traversed in 1898 by W. C. Mendenhall, who was attached as geologist to ‘military expedition No. 3,’ in charge of Capt. Edwin F. Glenn, Twenty-fifth Infantry, United States Army. Mendenhall’s explorations covered areas on the west shore of Prince William Sound and a route extending from Resurrection Bay to the head of Turnagain Arm, thence by way of Glacier and Yukla Creeks to Knik Arm, up the Matanuska Valley to its head, and thence northward to the Tanana. Mendenhall’s account of his explorations includes a description of the general geologic and geographic features accompanied by a topographic map on the scale of 1 to 625,000.”

Under the heading General Description of the District, the Matanuska River is described: “Matanuska River is tributary to Knik Arm, at the head of Cook Inlet. It rises on the western edge of the Copper River basin and flows between the Talkeetna Mountains on the north and the Chugach Mountains on the south. The Matanuska is about 80 miles in length and has a drainage basin of about 1,000 square miles. Its fall in the part of its course included in the area here described in detail is about 20 feet to the mile. This rapid fall gives it a swift current, because of which and of its being overloaded with sediment and consequently being in most places broken up into many shifting channels over an aggrading flood plain, it is not navigable. The fall is, however, so evenly distributed that there is no available water power. The principal tributaries of the Matanuska are Caribou Creek, Hicks Creek, Chickaloon River, and Kings River, of which the last two enter it within the area here described in detail. The other tributaries which it receives in this area are Coal, Carbon, Eska, and Moose creeks. It is a noteworthy fact that tributaries of the Matanuska all enter it from the north.”

After a couple of paragraphs describing the relative heights and characteristics of the mountains and the Matanuska River, Mendenhall’s report turns to vegetation in the Valley proper:

“Timber line in this area is at a general elevation of 2,000 to 2,500 feet, above which there is the customary growth of small bushes, moss, and grass. The trees include spruce, birch, and several kinds of cottonwood. The growth is in general not dense. Most of the spruce trees are under 12 inches in diameter, the largest one which the writers noted having a circumference of 5 feet. The timber is probably sufficient for any local demands that can now be foreseen, provided that forest fires which the dry climate favors are kept under control. There is no timber suitable for export. The more open birch forests, as well as the areas which have lately been burned, are covered with a dense growth of grass. These natural meadows are large enough to furnish feed for whatever stock is likely to be locally needed.”

Mendenhall’s report then describes accessibility of the Valley:

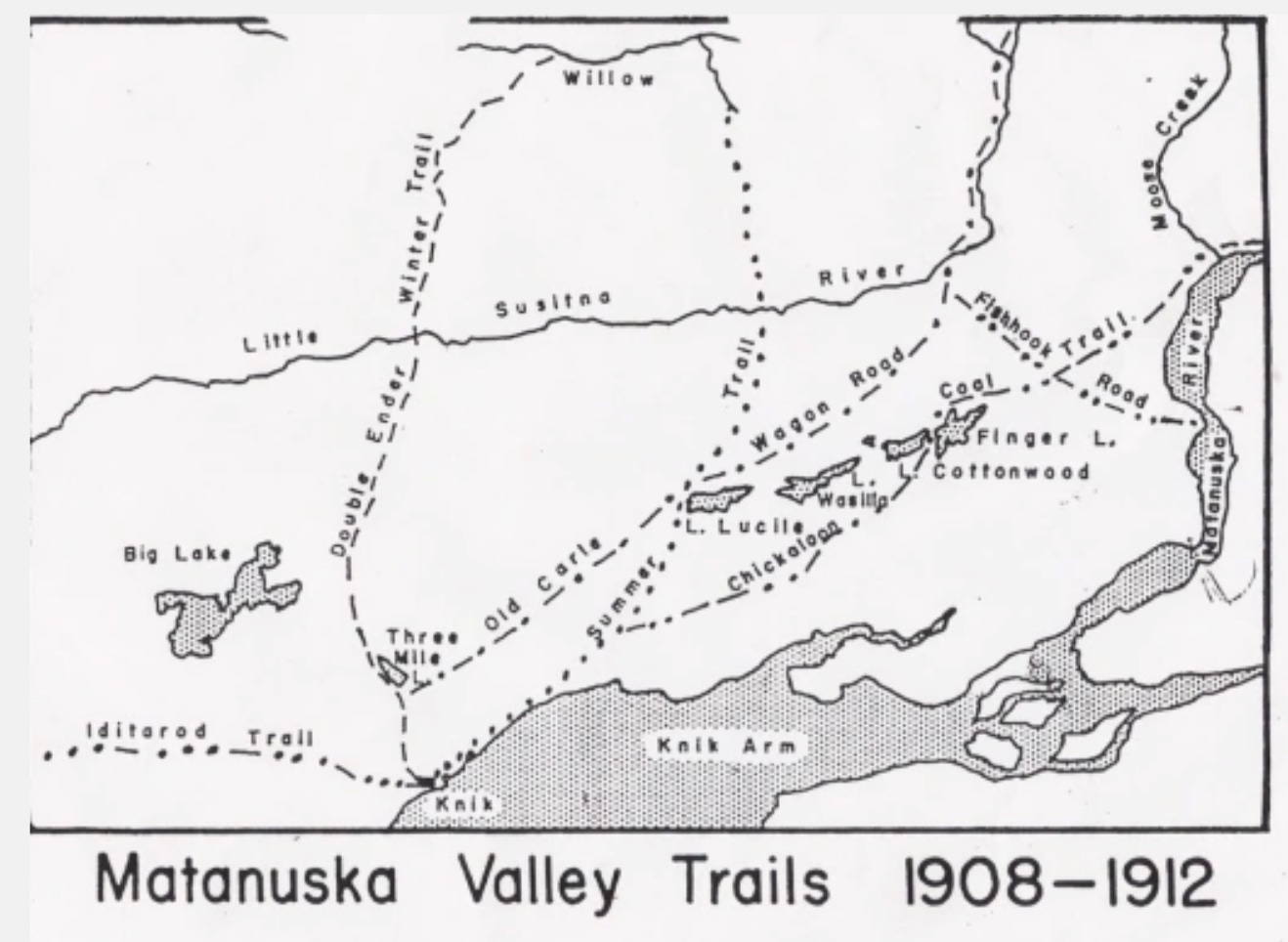

“The Matanuska Valley is at present reached from Knik, which is the head of navigation on Cook Inlet, and to which vessels of shallow draft can go at high tide. Near the lower end of Knik Arm there is a good anchorage, which ocean going vessels can reach at any stage of the tide except during the winter, when the whole upper part of Cook Inlet is frozen.

“There is a good horse trail from Knik to the upper end of Matanuska Valley, and the character of the ground and of the vegetation is such that this trail could be made into a wagon road at comparatively slight expense. It takes horses from one to two days to reach Moose Creek, depending on the load, and from a day to a day and a half to go from Moose Creek to Chickaloon River.

“At present freight can not be taken in while Cook Inlet is frozen, which is usually from October 15 to May 15, and passengers can reach the region during the winter only by going in from Seward with sleds.

“The Alaska Northern Railroad, which is now completed from Seward to Kern Creek, on the north shore of Turnagain Arm, a distance of 72 miles, is intended to reach Matanuska Valley, to which surveys have been made; some construction work has been done between Kern Creek and Knik Arm. According to the present surveys it will be about 150 miles from Seward to Chickaloon River. When this road is completed the Matanuska Valley will be easily accessible at any time of the year.”

This post is excerpted from this book: