Alaskan Barns

History on a Grand Scale

In his classic book, ‘An Age of Barns,’ author and illustrator Eric Sloane observes “The beauty of wood in the state of pleasing decay is one of Nature’s special masterpieces.”

In most parts of the territory of Alaska barns were few and far between, but as roadhouses were built along the trails they found it profitable to provide barns for the stock which traveled the trails, and as people saw the potential of agriculture in the north and the land grew more settled, barns were built to shelter livestock and to store feed and valuable equipment.

I have been collecting photographs and information about barns in Alaska for more than a decade, with an eye toward possibly writing a book about the history. Every time I think I have enough good examples I come across new (old) barns in surprising places, and it becomes apparent once again that the history of Alaskan barns is a subject as large and diverse as the land itself. I’ll share a few barns and some of the history below, and I might get that book written someday.

Some Alaskan barns were small, somewhat crude log shelters, while others were magnificent soaring structures built with the best lumber the federal government could buy and shipped north at considerable expense.

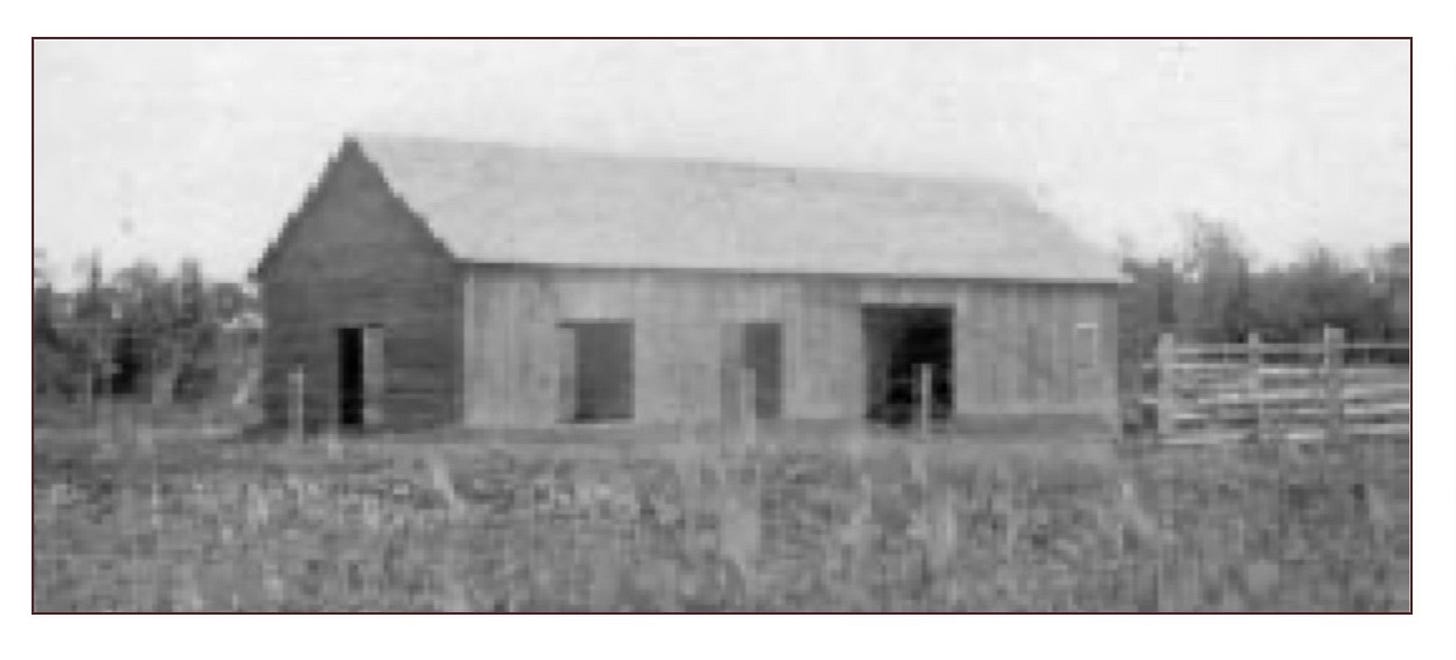

One of the first books published by Northern Light Media was The Matanuska Colony Barns: The Enduring Legacy of the 1935 Matanuska Colony Project, which shared the history of the stout square log-and-frame barns built for the 200 families who were transported north in 1935 as part of the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal. Nearly one hundred new communities were designed and developed by Roosevelt’s planners, but the largest, most expensive, and most audacious of them all was a government-sponsored farming community in Alaska’s Matanuska Valley. As part of each family’s farmstead a 36’ x 36’ x 36’ barn was built, mostly in the summer of 1936, and today around sixty of these iconic structures still dot the Valley near Palmer.

The history of barns in Alaska is much older than 1935, however, and a 12-page article in the current issue of Alaskan History Magazine highlights some of the great barns which played a role in Alaska’s past. Barns in Alaska, as in most places, come in all shapes and sizes, depending on the needs, location, availability of materials, and often on the skills of the builders.

The first shelters for animals in Alaska were likely the small crudely-built dog barns found at many trailside roadhouses for the passenger, freight, and mail dog teams which traveled the winter trails.

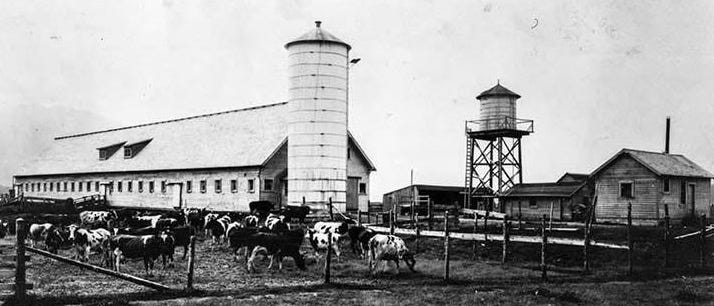

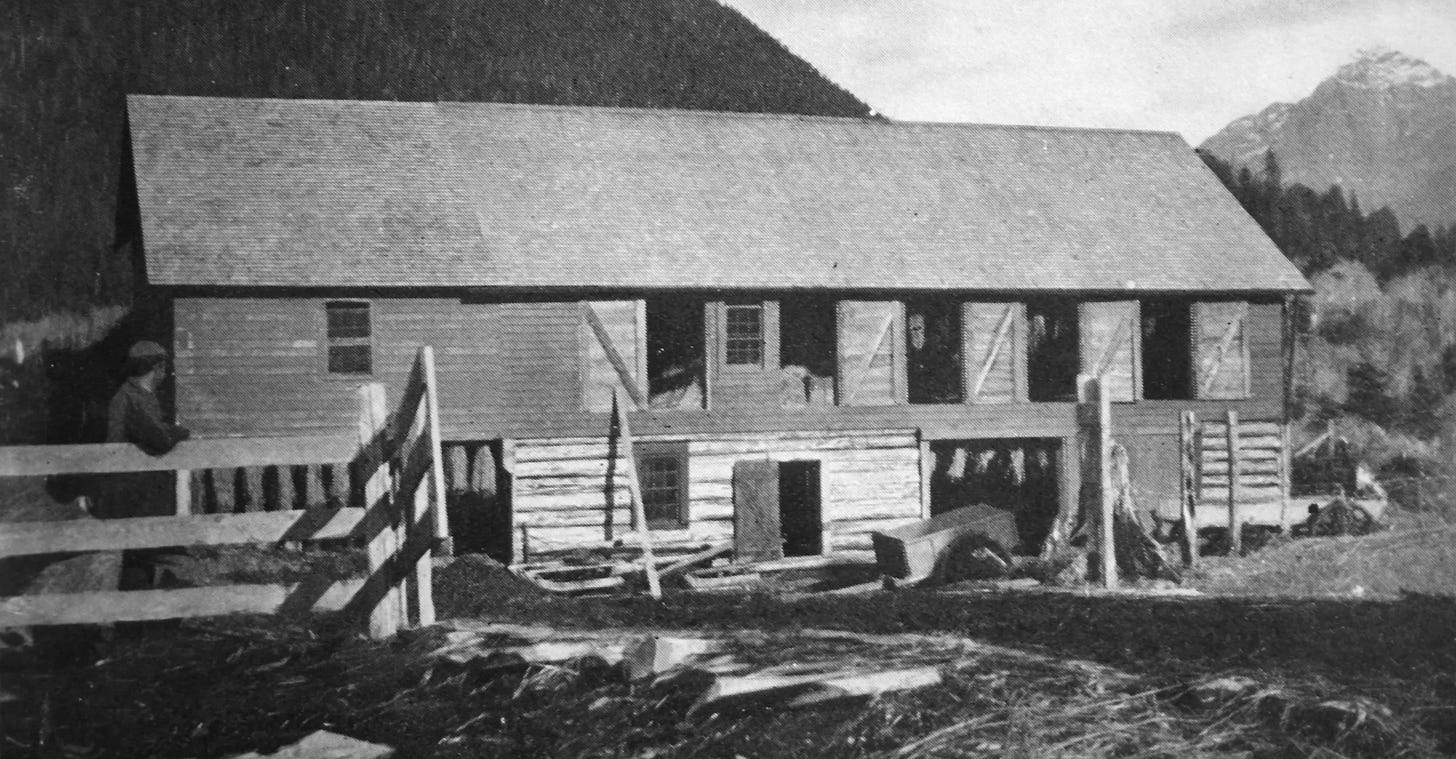

More than dozen families operated dairy farms in the Juneau-Douglas area from the 1890’s until the 1950’s, and large barns could be found on many of them, including the Juneau Dairy, the Pederson Dairy, the Alaska Dairy, the Mendenhall Dairy, the Lemon Creek Dairy, the Sunny Point Dairy and several more.

The large mining complexes which followed Joe Juneau and Richard Harris’ Gold Creek discovery of nuggets “as large as peas and beans,” and the growing government offices of the new territorial capital, along with related businesses, provided steady growth and a ready market for the dairies.

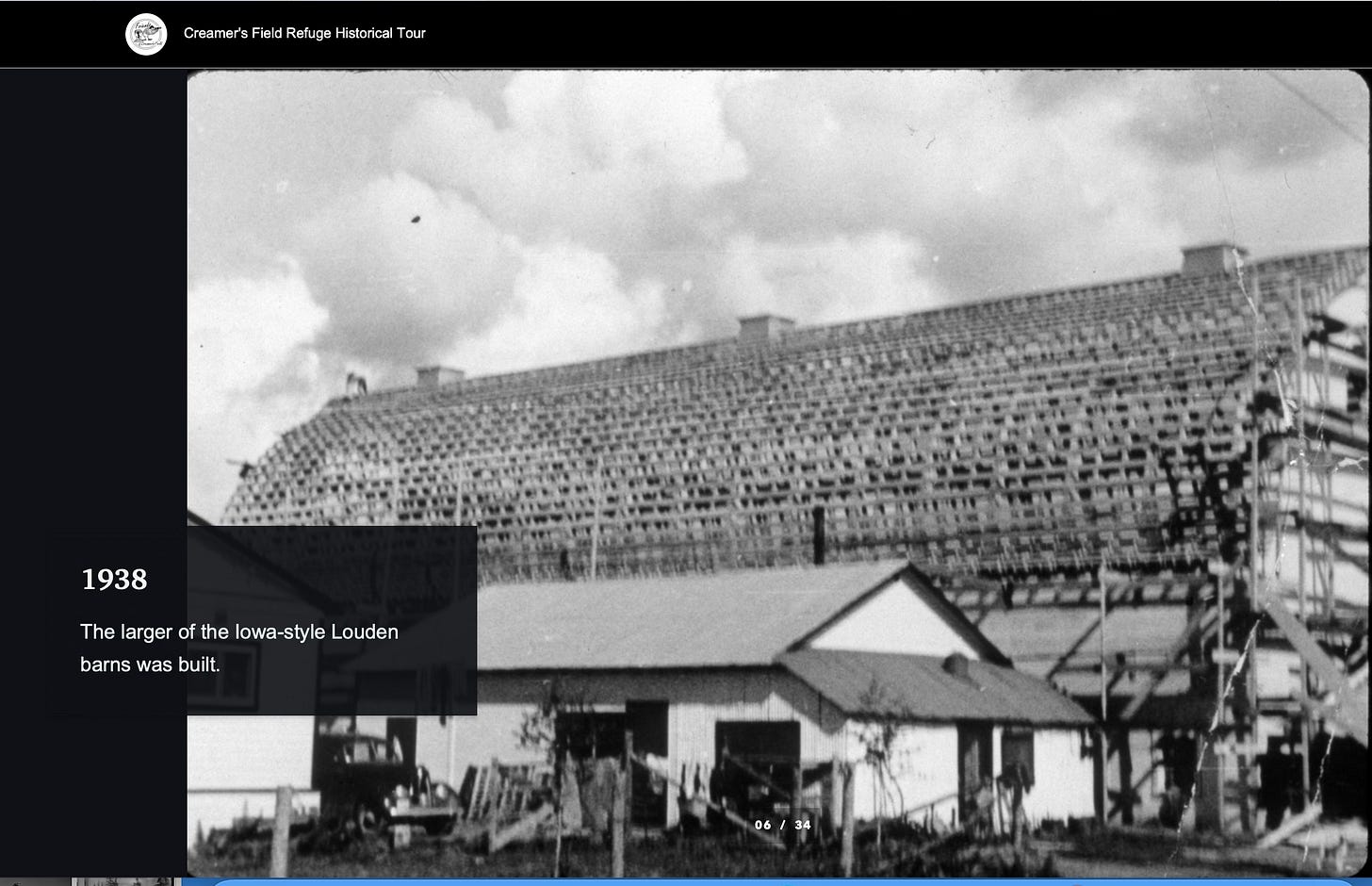

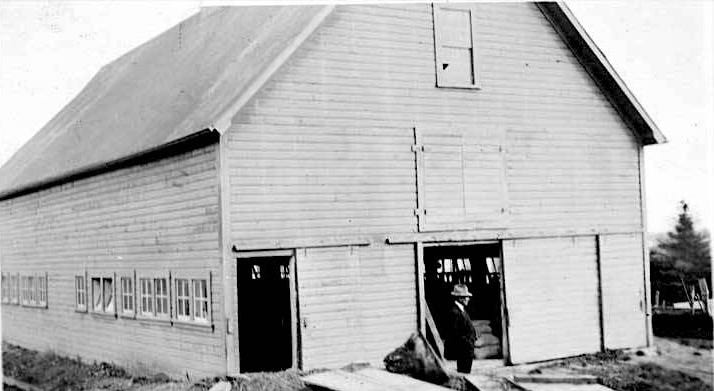

The two great Creamer’s Dairy barns are local icons in Fairbanks, anchoring the Creamer’s Field Migratory Waterfowl Refuge, over 2,200 acres of wildlife habitat within the urban area of Fairbanks. Shortly after the turn of the century, Charles Hinckley and his wife Belle started a dairy to serve the gold-rich outpost of Fairbanks. In 1928, they sold the dairy to Belle’s younger sister Anna and her husband, Charles Creamer.

The new owners renamed it Creamer’s Dairy, and they worked hard to modernize and expand the business, building two large Louden barns, designed by the renowned Louden Machinery Co. of Iowa. When the dairy ceased production in 1966 it was the largest and most successful dairy in Interior Alaska, and in 1977 the barns were admitted to the National Register of Historic Places.

In the early years of the 20th century the Valdez-to-Fairbanks Wagon Road, now the route of the Richardson Highway, was the primary route from tidewater to the interior of Alaska and the goldfields north of Fairbanks. Roadhouses along the 365-mile trail offered barns for the horses of the stage companies which traveled the route.

The Valdez Transportation Company, Orr Stage Company, Kennedy Stage Company and others took advantage of these facilities, including the heated barns at many roadhouses, including Wortman’s Roadhouse which advertised their “warm, roomy stables that can shelter 100 head of horses.”

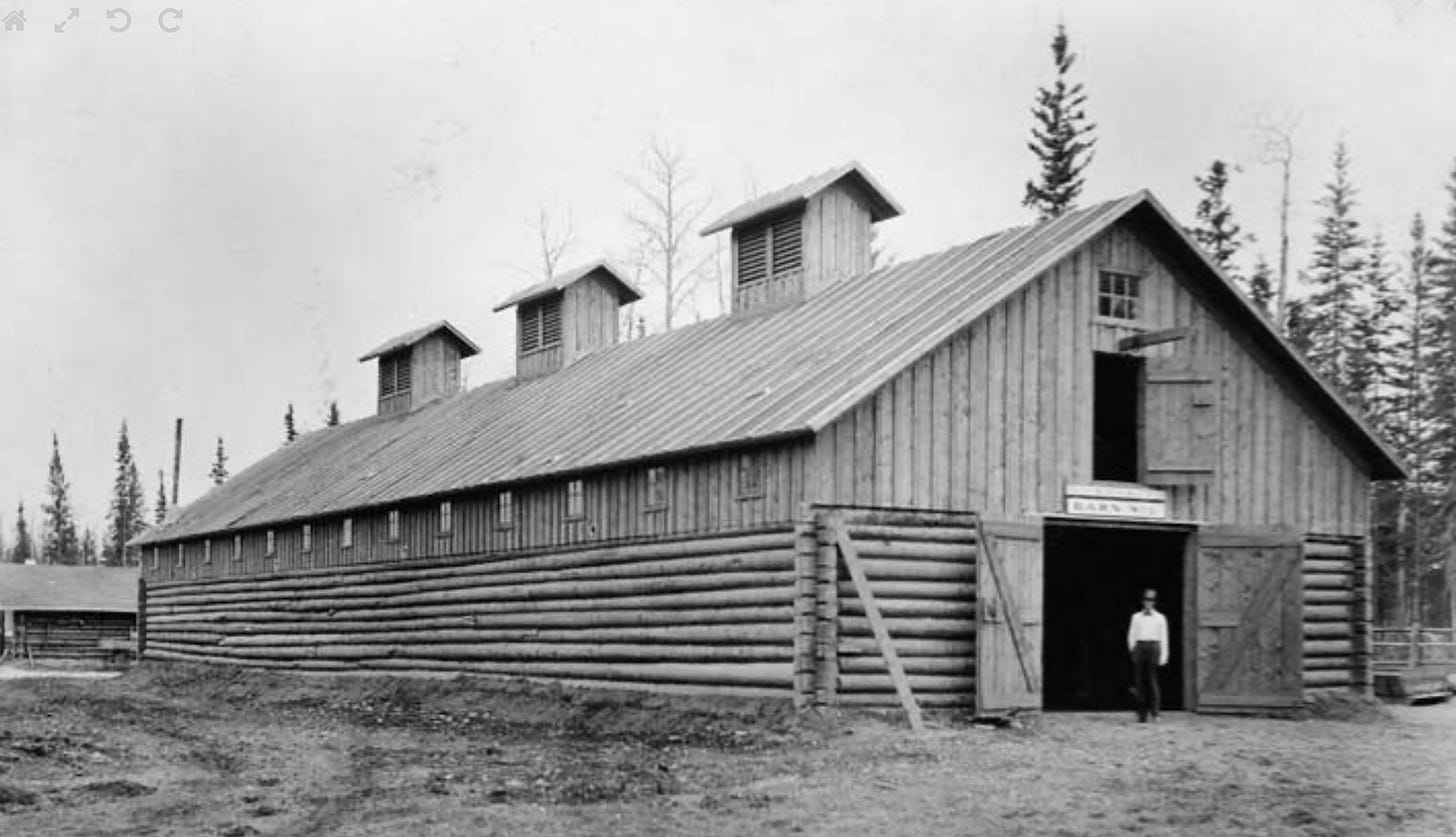

When the federal government built the Alaska Railroad, between 1902 to 1923, several large barns were built by the Alaska Engineering Commission for the stock which hauled freight, provided access and transportation, and served many other purposes in the construction project. Huge structures of log and frame were raised in Anchorage, Nenana, Fairbanks and other locations along the 500 mile route.

Returning to those great barns of the Agricultural Experiment Stations which sprang up across the territory, beginning in 1898 in Sitka, additional barns were built at Fairbanks, Kenai, Kodiak, Matanuska and several other sites.

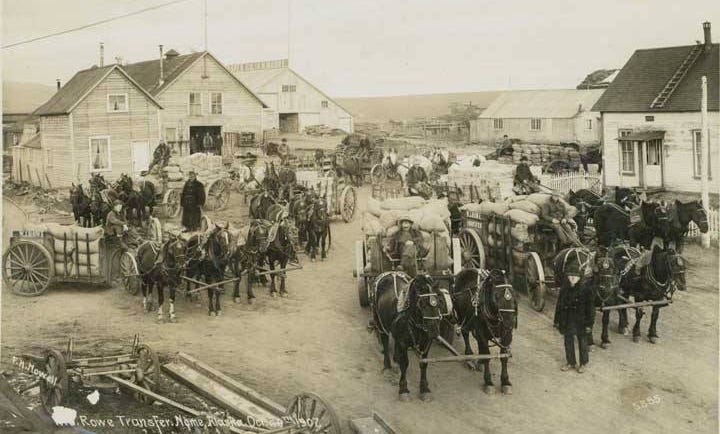

In the photo below from Nome, the sign across the top of the large barn in the background reads “…Transfer Co. A. H. Moore,” while lettering on the wagon in front and at the bottom of the photo is of the W. J. Rowe Transfer and Freighting Company.

“Inside a barn is a whole universe, with its own time zone and climate and ecosystem, a shadowy world of swirling dust illuminated in tiger stripes by light shining through the cracks between the boards. Old leather tack, lengths of chain, rope, and baling twine dangled from nails and rafters and draped over stall railings. Generations of pocketknives lay lost in the layers of detritus on the floor.”

― Carolyn Jourdan, Heart in the Right Place

Very cool!

Helen Hegener’s tribute to Alaskan barns is not just historical it’s deeply devotional. Each structure she evokes feels less like a building and more like a heartbeat preserved in timber. These barns weathered, vast, sometimes crude, sometimes majestic carry the breath of animals, the sweat of settlers, the quiet dignity of survival. What’s most human here is her reverence: not for perfection, but for endurance. She doesn’t catalogue barns she listens to them. In her care, they become memory keepers, guardians of a land that asked much and gave little, yet still offered shelter. Her work reminds us that history lives not in grand monuments, but in the humble spaces where life was made and kept.