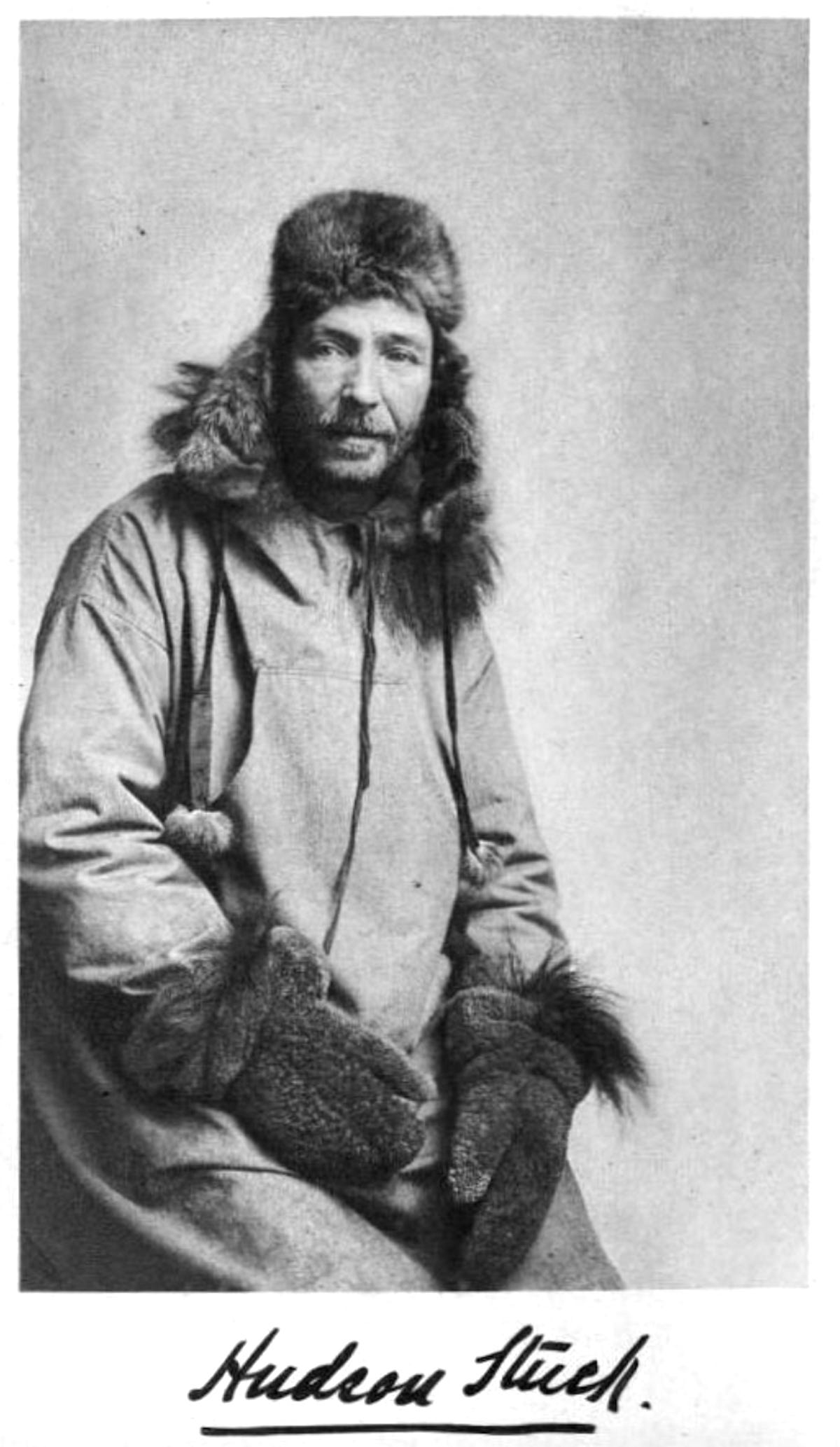

Hudson Stuck

"Archdeacon of the Yukon and Tanana Valleys and of the Arctic regions to the north of the same"

In The Alaskan Missions of the Episcopal Church, A brief sketch, historical and descriptive, by Hudson Stuck, D.D., published in 1920 by the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, the following lines open Chapter VI, By Dog-Sled or Launch:

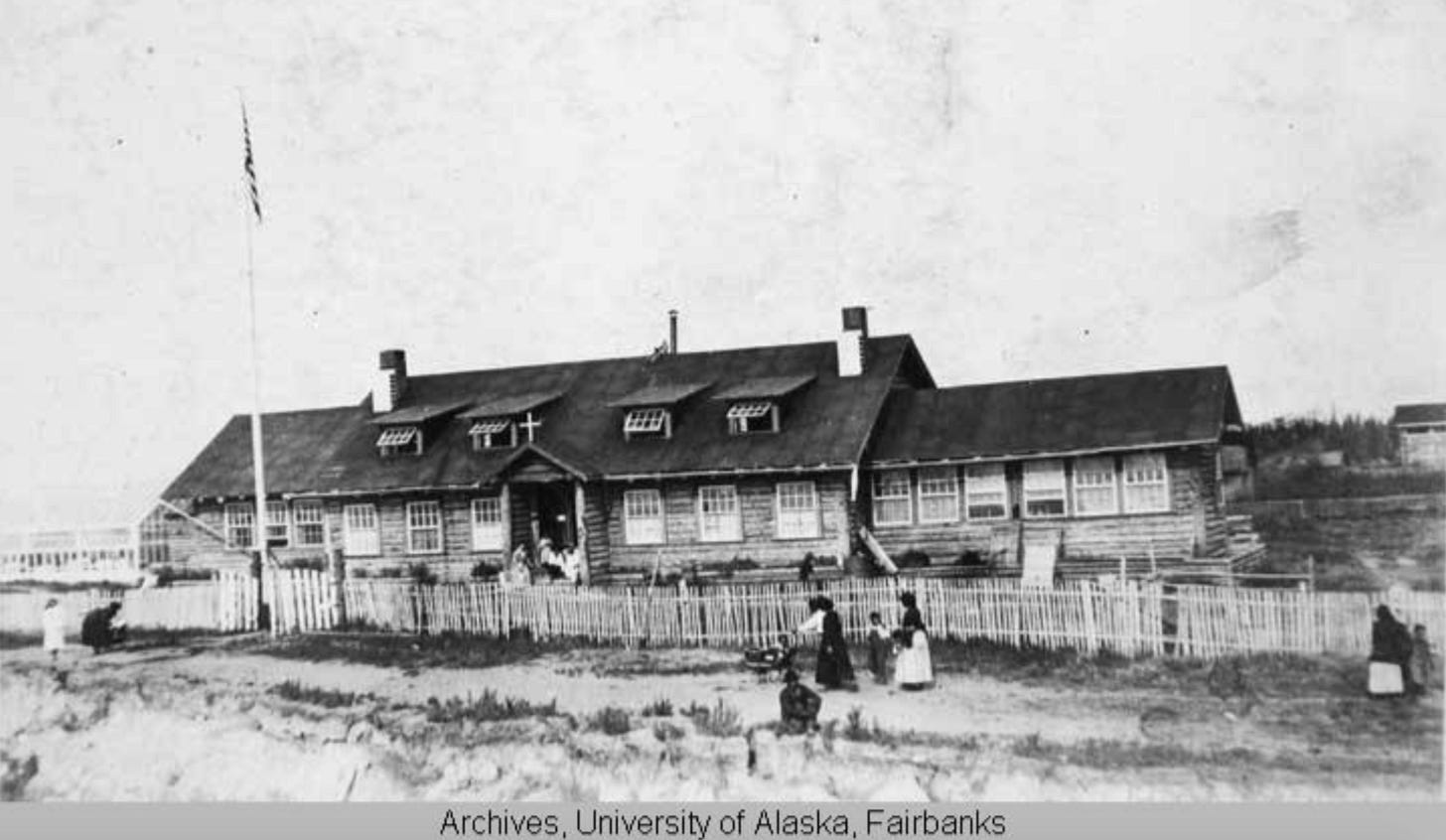

“With the building of Fairbanks it became evident that the work of the Church in the territory was grown too large for the constant personal supervision of the Bishop [Peter Trimble Rowe], and in this year (1904) the present writer, then Dean of St. Matthew's Cathedral, Dallas, Texas, responded to an appeal of the Bishop, mainly with a view of relieving him of his winter journeys. He went to Fairbanks that summer with a commission as ‘Archdeacon of the Yukon and Tanana Valleys and of the Arctic regions to the north of the same’--a sufficiently wide scope for any man's wanderings and charge.”

After a description of his founding of St. Matthews Mission and Hospital in Fairbanks, the writer, Hudson Stuck, notes, “There began in 1904 a series of archdiaconal winter journeys with a dog sled, each covering from 1,500 to 2,000 miles, in which the populated parts of the whole Yukon basin were reached and the whole Arctic coast was visited; twelve winters having been so spent at this writing.”

Those winter journeys over a territory of 250,000 square miles would result in one of the most fascinating books of northland travel ever written, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled, published in 1914. The book detailed Stuck’s missionary activities as he traveled between the villages of northern Alaska, establishing missions at at Nenana, Chena, Salcha, Tanacross, and Allakaket, and it would be the first of his five books on his travels and missionary work in Alaska.

Traveling incessantly by dogsled in winter and boat in summer, Stuck ministered to miners and woodchoppers of Alaska's Interior and championed the Indians and Eskimos. He was noted as an active defender of the region's indigenous peoples, whose contact with "low-down whites," he believed, doomed them to eventual extinction, and he always emphasized the value of education.

The son of James and Jane (Hudson) Stuck, Hudson was born in Paddington, London, England, on November 11, 1865. He attended Westbourne Park Public School and King's College. In 1885, eager for "wide-open spaces," heralded in a railway advertisement, he tossed a coin: heads for Australia, tails for Texas. It landed tails, and Stuck, in a phrase of the era, was G.T.T.-"gone to Texas.” He emigrated to the United States in 1885, settling in Texas, where he worked as a cowboy near Junction City and taught in one-room schools at Copperas Creek, San Angelo, and San Marcos.

In 1889 Stuck entered the theology department of the University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee, graduating as an ordained priest in 1892. He served for two years at Grace Church in Cuero, Texas, before moving to St. Matthew's Cathedral, Dallas, where he served as dean for several years. His notable accomplishments during this time included founding a home for indigent women, a boys’ school, and a children’s home; and in 1903 he pioneered the first state law to curb the “indefensible abuse” of child labor.

After moving to Alaska in 1904, Hudson Stuck became a relentless force for advancing the Espiscopal church’s mission in the Last Frontier. In 1905, Rev. Charles E. Betticher, Jr joined Stuck in Alaska as a missionary, and the two men worked together for the next decade, establishing schools, hospitals, and churches across the northernmost wilderness. While the Reverend Stuck had a special interest in the indigenous peoples, he also wanted to reach the scattered population of miners, prospectors, roadhouse operators and other frontiersmen. Stuck started the Church Periodical Club, which collected and distributed periodicals to all the missions and other settlements. Based in Fairbanks, it provided much more than just church literature, and was often the only reading material available. Stuck explained in 1920, “Church people generally throughout the United States were brought into line, and a stream of weekly and monthly publications began to pour into Fairbanks, and to go out again to the remotest corners of the country, until the number handled annually rose above twenty thousand. Many an isolated prospector depends to this day for his winter reading upon packages supplied from the Fairbanks mission.”

In 1908 Hudson Stuck acquired a small riverboat, the Pelican, which he used on the Yukon River and its many tributaries, ranging several thousand miles every summer to visit the Athabascan Indians in their fishing and hunting camps. These travels he also later described, in his book Voyages on the Yukon and its Tributaries (1917). In The Alaskan Missions of the Episcopal Church, Stuck wrote glowingly of his Pelican:

“Of all aids in the direction and supervision of enterprises now widely scattered throughout the interior, the launch Pelican, built and brought to the Yukon in 1908, at an expense of nearly $5,000, has been the greatest; indeed without some such craft the visiting of all these stations in any one summer would be an impossibility. The Pelican at this writing has made twelve seasons' cruises, ranging from i,800 to 5,200 miles each summer, and has travelled an aggregate distance of upwards of 30,000 miles on the Yukon and its tributaries. She is a comfortable ‘glass cabin cruiser’ with a draught of sixteen inches and a speed of about nine miles an hour, has accommodations for sleeping and cooking and a gasoline capacity of 250 gallons, depots of gasoline being maintained at several central points so that prolonged cruises lasting most of the summer can be made in her. The only mission in the interior that she does not visit is the Tanana Crossing, her one attempt to reach that point having been defeated by a violent sudden freshet which filled the river with driftwood. She has never had professional pilot or engineer, but has been handled altogether by native help. An appropriation of $500 per annum, which about pays for her gasoline and lubricating oil, is made by the Department of Missions; chiefly contributed by the boys at several well-known preparatory schools in New England.

“This craft enables the Bishop and the archdeacon to visit, not only the mission stations but the scattered camps of natives all along the rivers, engaged in their summer salmon fishing; to stay at any place as long as may be necessary, to leave when it is convenient. The traveller dependent upon steamboats who should break his journey at mission stations would spend most of the short season waiting for boats, and would not be able to visit the camps and riverside cabins at all. She has again and again been useful in conveying desperately injured persons to speedy medical aid, in taking children to the schools at Nenana and Anvik, and regularly transports quantities of reading matter for distribution.”

Stuck had experience in mountain climbing, including the Canadian Rockies and the dormant volcano Mount Rainier in Washington state. In 1907 he wrote of the great Denali, “I would rather climb that mountain than discover the richest gold-mine in Alaska.”

In 1913, at the age of 50, he recruited the respected wilderness guide and musher Harry Karstens to join an expedition to the summit of Denali (then known as Mt. McKinley). Other members were Walter Harper, of Alaska Native and Irish descent, Tennessee native Robert G. Tatum, and two student volunteers from the mission school at Nenana, Johnny Fred (John Fredson), and Esaias George.

The small party left Nenana on March 17, 1913 and Stuck described their base camp: “Our approach was not directly toward Denali but toward an opening in the range six or eight miles to the east of the great mountain. This opening is known as Cache Creek. …We pushed up the creek some three miles more to its forks, and there established our base camp … at about four thousand feet elevation.”

The men cautiously crossed the treacherous, crevasse-ridden Muldrow Glacier, with Stuck noting, “The work on the glacier was the beginning of the ceaseless grind which the ascent of Denali demands.”

He described their dangers: “It took several days to unravel the tangle of fissures and discover and prepare a trail that the dogs could haul the sleds along. Sometimes a bridge would be found over against one wall of the glacier, and for the next we might have to go clear across to the other wall. Sometimes a block of ice jammed in the jaws of a crevasse would make a perfectly safe bridge; sometimes we had nothing upon which to cross save hardened snow. Some of the gaps were narrow and some wide, yawning chasms. Some of them were mere surface cracks and some gave hundreds of feet of deep blue ice with no bottom visible at all.”

The climbing party reached the summit of Denali on June 7, 1913. When they returned to base camp Stuck sent a messenger to Fairbanks, and their groundbreaking achievement was announced to the world on June 21, 1913, by The New York Times.

Harry Karstens, Stuck’s co-organizer, went on to become the first superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park when it was established in 1917. Twenty-one year old Robert Tatum, from Tennessee, was teaching at the mission school at Nenana when he met Stuck on one of the Archdeacon’s visits to the mission and was engaged as a camp cook for the expedition.

Walter Harper, the Irish-Koyukon Alaska Native, was the first to reach the summit of Denali on June 7. After the climb, Harper continued his formal education, and he planned on going to medical school. In September, 1918 Harper married Frances Welles with Archdeacon Stuck officiating, and he and his wife boarded the ill-fated steamer SS Princess Sophia, en route to Seattle, for their honeymoon. The ship ran aground on a reef in a snowstorm, was broken up in a gale, and sank on October 25, 1918. All 268 passengers and 75 crewmen were lost in one of Alaska’s greatest sea tragedies.

After his successful climb, Hudson Stuck worked as an Episcopal priest in Alaska for the rest of his life, writing five books, in part to reveal the abhorrent exploitation of the Alaska Native peoples that he witnessed in his work. He did not mince words in describing the situation, as shown in this foreword to his first book, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled (1914), and his stout and heartfelt plea stands as his true legacy to Alaska’s history: “There are, of course, those who view with perfect equanimity the destruction of the natives that is now going on, and look forward with complacency to the time when the Alaskan Indian shall have ceased to exist. But to men of thought and feeling such cynicism is abhorrent, and the duty of the government towards its simple and kindly wards is clear.

“A measure of real protection must be given the native communities against the low-down whites who seek to intrude into them and build habitations for convenient resort upon occasions of drunkenness and debauchery, and some adequate machinery set up for suppressing the contemptible traffic in adulterated spirits they subsist largely upon. The licensed liquor-dealers do not themselves sell to Indians, but they notoriously sell to men who notoriously peddle to Indians, and the suppression of this illicit commerce would materially reduce the total sales of liquor.

“Some measure of protection, one thinks, must also be afforded against a predatory class of Indian traders, the back rooms of whose stores are often barrooms, gambling-dens, and houses of assignation, and headquarters and harbourage for the white degenerates—even if the government go the length of setting up co-operative Indian stores in the interior, as has been done in some places on the coast. This last is a matter in which the missions are helpless, for there is no wise combination of religion and trade.

“So this book goes forth with a plea in the front of it, which will find incidental support and expression throughout it, for the natives of interior Alaska, that they be not wantonly destroyed off the face of the earth.”

In October, 1920, barely a month before his 55th birthday, Hudson Stuck, a lifelong bachelor and the venerable Archdeacon of the Yukon, died of bronchial pneumonia in Fort Yukon. At his own request he was buried in the local cemetery, still a British citizen. ~•~

Hudson Stuck published five highly collectible books about his years in Alaska, two of which were edited by Maxwell Perkins, the legendary Scribner's editor who also edited Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe. They are available to read online or download.

• Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled: A Narrative of Winter Travel in Interior Alaska (1914)

• The Ascent of Denali: A Narrative of the First Complete Ascent of the Highest Peak in North America (1914)

• Voyages on the Yukon, and Its Tributaries: A Narrative of Summer Travel in the Interior of Alaska (1917)

• A Winter Circuit of Our Arctic Coast: A Journey with Dog-Sleds Around the Arctic Coast of Alaska (1920)

• The Alaskan Missions of the Episcopal Church, A brief sketch, historical and descriptive (1920)