“The Alaskan roadhouse is a trail or roadside hotel. It deserves and has earned the high regard that all Alaskan and northern travelers have for the ‘roadhouse.’”

~William E. Gordon, in Icy Hell (Wm. Brendan & Son, 1937)

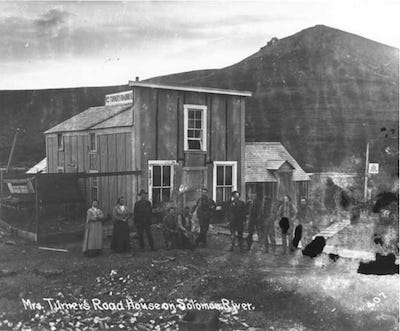

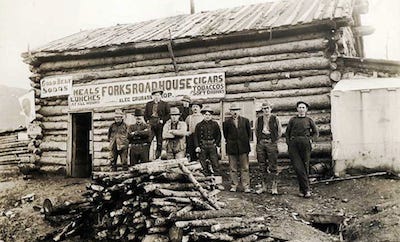

The roadhouses of Alaska and the Yukon Territory in Canada were a creation of the times in which they flourished, a time when men and women traveled slowly and laboriously over thin trails through an almost unimaginable wilderness, coping day after day with hostile weather, treacherous river crossings, and mountains which loomed and only grudgingly presented high passes through which to cross.

At the end of a long day’s journey the lights of a roadhouse in the distance could only be a welcome sight. No matter how rough the accommodations, the roadhouse signaled warmth and food and a place to rest for a few hours. There would be a shelter for one’s team, be they dogs or horses, hopefully a barn with good feed and fresh hay. The roadhouse proprietor would have news of the trail ahead, and he would be ready to listen to the tales of the trail just crossed, so he could pass the information along to the next travelers who stopped there.

The network of roadhouses along Alaska’s far-flung trails was an interconnected lifeline which made travel possible, and the role they played in the history of the north cannot be overstated. Hudson Stuck described a common travail of northern travel in A Winter Circuit of our Arctic Coast, A Narrative of a Journey with Dog Sleds [Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920]: "We awoke next morning to changed conditions; two or three inches of new snow lay on the earth. And all day long it snowed and a drifting wind filled up the trail and sledding grew heavier and heavier. The toboggan became such a drag in the wet snow from the remains of yesterday's ice, lingering notwithstanding repeated beatings, that by and by we set it bodily on top of the sled and hitched the ten dogs to the double load with advantage. It took us five hours to make the eighteen miles to the next roadhouse, and here we stayed for lunch and took the toboggan into the house and thawed off the ice in front of the stove."

Judge James Wickersham’s travels across Alaska’s Third Judicial District covered 300,000 square miles, and he kept detailed diaries and often described the roadhouses he frequented, such as this one northeast of Circle City: “Webber's one-room log tavern with a dirt floor stood at the edge of a dense forest. The side walls of the cabin, built of small round logs, were head high, and the central roof log was just above the outstretched fingertips. The tavern was about ten by sixteen feet square inside. It was finished with one clapboard door hung on wooden pins, and one window sash.

“The dining table consisted of boards nailed to poles, about three feet long, driven into auger-holes about four feet apart just below the window. Two pole bunks of similar design adorned the back wall. The dirt floor was spattered with grease from the stove. There was one chair of riven slab set on three pole legs. The two other chairs were boxes, one marked in large letters, 'Hunter's Old Rye,' and the other, 'Eagle Brand Milk.' A dog stable, much smaller than the tavern, stood alongside. These buildings and their accommodations for travelers were typical of those along the Yukon River Trail.”

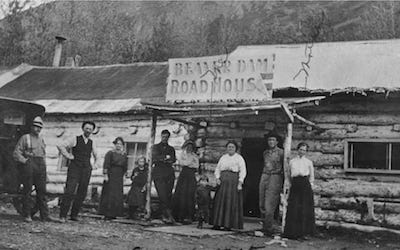

As dog team, stage, and foot traffic increased on these trails between far-flung towns and villages, more and more roadhouses sprang up, built by enterprising individuals and offering a place to rest and recuperate from the harsh rigors of the trail. Through the center of the territory the Trans-Alaska Military Trail and Wagon Road became the Valdez-Eagle Trail, which spawned the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail which then became the Richardson Highway, the first actual road in Alaska. As the primary route from the Pacific coast to Interior Alaska, the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail sprouted more roadhouses than any other route, including some of the most colorful and iconic: Sullivans, Rika’s, Sourdough, Tiekhell, Beaver Dam, Gakona, Black Rapids, Comfort, Ptarmigan Drop, Wortman’s, Paxson, Yost’s, Tsaina, Tonsina….

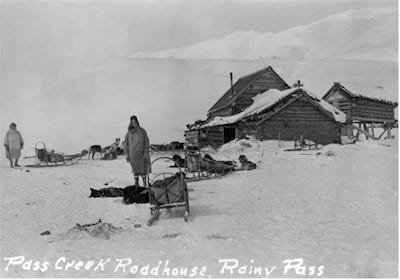

Only one other route produced such a litany, the famed Iditarod Trail; one listing names almost 40 roadhouses in the first 500 miles to the Iditarod gold fields. That’s a roadhouse approximately every twelve miles. In 1908 Col. Walter L. Goodwin provided the initial exploration of the Iditarod Trail and a first-hand description of the route, and he included a listing of the many roadhouses along the trail from Seward to Iditarod, approximately 10 to 20 miles apart and including Glacier Creek, Raven Creek, Knik, Susitna, Skwentna, Happy River, Pass Creek, Rainy Pass, Rohn River, Farewell, Kuskokwim, Tacotna, and many others, but he makes only the briefest mentions of two roadhouses further north in his 1908 report.

The first is just after the party leaves Ophir Creek: "In forty miles we arrived at Dishakaket, an Indian Village on Shagaluk Slough (to the Yukon) and are told it is 86 miles to Kaltag, but which I find to be but 59 miles. Here are 100 or more natives and some dozen white people, with two stores, a saloon and a roadhouse. This is thought the be the head of navigation, but later boats have been up the Innoko and Ditna to Hanes Ldg., said to be forty miles from Gane Creek."

The second mention: "From Dishakaket we follow the very crooked trail through rolling, swampy, sparsely timbered country to the Kaiyuh Slough where there is a roadhouse. This place is some three miles up the river and up the slough, and is said to be 18 miles from Kaltag. This I found to be about 14.5 miles while the Alaska map shows it to be by scale 24 miles."

Back on the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, the Paxson Roadhouse stood for many decades as a popular landmark for travelers and locals alike, going through at least three locations in the area.

In 1896 Alvin J. Paxson came to Alaska on his way to the Klondike to look for gold. He never struck it rich, but he made a living prospecting, carrying the mail, and working at a number of mining camps in the Yukon River drainage.

Paxson worked in a trading post, helped set up a store, and in 1906, he built his first roadhouse eight miles south of Isabel Pass, on the then-new Valdez-Fairbanks Trail. The Timberline Tent Roadhouse consisted of a small cabin and two tents, and for additional income Paxson outfitted miners bound for the nearby gold camps. The following year, as the Alaska Road Commission was working on a new section of the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail which would bypass his first location, Paxson selected a new site about three miles south of Summit Lake and built a 30-foot by 80-foot two-story log lodge. With his new roadhouse located in an area well-sheltered by tall spruce trees from the harsh winds blowing down out of Isabel Pass, business was good, a Washington Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS) telegraph station was built, and when the Orr Stage Line made Paxson's Roadhouse a regular stop, a large barn, the first of several, was added to the roadhouse site. Alvin Paxson became known for his hospitality, and a small community began to grow around his roadhouse. Trails to the new mining areas of Slate Creek and Valdez Creek made the roadhouse a junction and supply point. A post office opened in 1912 and Alvin Paxson was appointed postmaster.

In Alaska's Wolf Man: The 1915-55 Wilderness Adventures of Frank Glaser, author Jim Rearden describes a trip Glaser undertook in 1915, when he passed through the area: "At Paxsons we found a big roadhouse, a signal corps station, and an Indian village consisting of seven or eight cabins. Sled dogs ran loose in the village. In the fall sockeye salmon ran into Summit Lake via the nearby Gulkana River after swimming up from the Copper River. Almost every year a huge migration of caribou passed nearby. The trail climbed gradually to Summit Lake in Isabel Pass. Though it was after mid-May, seven-mile-long Summit Lake at 3,210 elevation was still frozen."

In 1916, poor health forced Alvin Paxson to leave Alaska for a warmer climate, but the small community kept the name of its founder.

One of the most well-known roadhouses in Alaska is the Talkeetna Roadhouse, in the railroad town of Talkeetna, built sometime around 1916-17 by brothers Frank and Ed Lee. They were from Michigan, and they made their living freighting supplies to the gold mines in the Peters Hills, Cache Creek, and Dutch Hills areas west of the Susitna River, in the southernmost foothills of Mt. McKinley.

Talkeetna’s first businesswoman, Isabella “Belle” Grindrod Lee McDonald, arrived in Talkeetna in 1917 and married Ed Lee, Frank’s brother, a year later. With her brother-in-law Frank Lee as her head freighter, Belle developed the Talkeetna Trading Post, a freighting service, stable, blacksmith shop, and the beginnings of a roadhouse, located half a mile west of the present-day Talkeetna Roadhouse, at the edge of the wide Susitna River. After Ed died in 1928, Frank and Belle continued the freighting business together, and at some point the precursor of the current roadhouse came into service.

In her 1974 book, Talkeetna Cronies, Nola H. Campbell, who owned and operated the Fairview Inn for a time with her husband John, wrote of Belle McDonald’s Talkeetna Trading Post, the forerunner of the Talkeetna Roadhouse: “Belle’s place was like home to many tired, weary and hungry men who came in from the hills. The walls were covered with hanging fur pelts of many kinds: mink, marten, weasel, lynx and wolf. Gold scales, beaver skins, blankets and kits were stacked in the corners, and traps and gear was piled around.”

Today’s Talkeetna Roadhouse welcomes travelers from around the world.

The Gakona roadhouse, dated from the first buildings constructed on the site, is the oldest still-operating roadhouse in Alaska. Originally called Doyle's Ranch, the Gakona Roadhouse was constructed by Jim Doyle, who homesteaded the site in 1902 on the banks of the fast-flowing Gakona River, which joins the mighty Copper River a few hundred yards downstream. His homestead was at mile 132 of the Trans-Alaska Military Road, which was the name of the then-new Valdez-to-Eagle Trail, built by the U.S. Army to link its post at Fort Liscum, near Valdez, with Fort Egbert, at Eagle on the Yukon River. The Valdez-to-Fairbanks Trail branched north near the site, making the junction of the two trails an excellent location for a roadhouse.

In 1910, the roadhouse become the main stop for the Orr Stage Company, and Doyle added a blacksmith shop and a barn that could hold up to a dozen horses. He also raised oats and hay on over sixty acres of fields. Jim Doyle sold the roadhouse in 1912, and the property went through the property had several owners, including the Slate Creek Mining Company.

In 1926 Arne N. Sundt, a director of the Nabesna Mining Company, discovered that the manager of the Slate Creek mine, a fellow named Elmer, was sidetracking the gold which should be going to the mine owners. In a 1993 interview for the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Oral History Program, Arne N. Sundt's widow, Henra Sundt, explained what happened next: "Arne put on the only suit that he ever owned," and traveled to the offices of the mining company and told them what was transpiring. They told Arne he "could just take over the place as Elmer hadn't sent them one ounce of gold in years!"

Arne made an agreement to mine the company's holdings on Slate Creek and send them a percentage, and they sold the roadhouse to him as part of the deal. When Arne got back to Gakona and confronted Elmer with the news, "Elmer got pretty upset and pulled a gun on him, but Arne just reached out and took the gun away from him." Henra explained, "[Elmer] was just a little guy, but my husband was six feet tall! So Elmer left, but he stayed around the country, mining his own claims on Slate Creek."

In 1929 Arne Sundt built a new roadhouse, much larger than its predecessor, in an L-shaped, gable-roofed plan, with 9 private rooms, a bunkhouse on the upper floor, two bathrooms, a general store, and a post office. He also built a separate owner’s residence, two cabins, a wagon repair shop, and other buildings. Arne and Henra, who had traveled to Alaska from Norway in 1928 to marry Arne, ran the roadhouse together for 22 years, until Arne's untimely death from a heart attack in 1949. When he died, her friends said Henra should sell the roadhouse, but she felt running the roadhouse would provide a good living for her and her children, and she prospered, raising two sons and a daughter, finally selling the roadhouse in 1979. All of the buildings on the site - all but two of them made of logs - have been subsequently added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The Dexter Roadhouse, 62 miles south and east of Nome, was a key point on the Iditarod Trail in 1925, when men and dogs raced blizzard conditions to bring a life-saving antitoxin to the gold rush city of Nome. The roadhouse was situated at the end of two of the biggest challenges on the trail: the shifting pack ice of Norton Sound and the harrowing climb to the summit of what was known locally as Little McKinley. Both would be crossed in a raging blizzard by champion dog driver Leonhard Seppala and his champion racing team of Siberian Huskies, with the inimitable leader Togo finding the way. The tough little Siberian’s efforts won him a place in history, and the landmark roadhouse won a mention in Gay and Laney Salisbury’s book about the serum run, The Cruelest Miles: The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race Against an Epidemic: “With few reserves to call on, the team began to stumble from exhaustion. But they did not stop, and strained up the final ascent, then raced three miles down to Dexter’s Roadhouse in Golovin.”

Around 1890, John Dexter, one of the employees of the nearby Omalik mines, married an Eskimo woman and established a trading post and roadhouse that became the center for swapping prospecting information for the entire Seward Peninsula. There were silver mines on the Fish River, and when gold was discovered at Council in 1898 Golovin became a supply point for the gold fields, but two years later, when gold was discovered in what is now Nome, much of the activity moved there and Golovin’s population declined.

The Sullivan Roadhouse dates to the winter of 1905-06, when gold rush pioneers John and Florence Sullivan built a log roadhouse on the winter shortcut known as the Donnelly-Washburn Cut-off, which left the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail and ran southeast to the Delta River, cutting 35 miles off the route. They constructed a long, low 20' x 60' cabin with a unique open 'dogtrot' in the middle section which allowed mushers to drive their teams under the shelter of the sod roof before unloading passengers and freight, or unhooking their dogs.

The following year the Alaska Road Commission changed the route of the winter cut-off and the Sullivan Roadhouse was suddenly four miles off the trail. The Sullivans resolutely disassembled their roadhouse, hauled it log by log to the new location, and rebuilt their roadhouse, adding a metal roof and enclosing the dogtrot middle section. Additional buildings were added, including a barn, a blacksmith shop, and a guest cabin.

With welcoming owners and comfortable accommodations, the Sullivan Roadhouse was a favorite stop for the freighters on the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, and business was good until around 1920, when the main trail, by then known as the Richardson Highway, became the favored route. The Sullivans packed their belongings and moved to Fairbanks in 1923, and the old roadhouse sat abandoned for the next seven decades.

In 1997 the Sullivan Roadhouse, the oldest existing roadhouse in Interior Alaska, was once again disassembled and moved, this time to Delta Junction, where it was lovingly refurbished, refurnished, and became the state’s premiere roadhouse museum, showcasing the history of the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail with a large collection of historical artifacts and photographs.

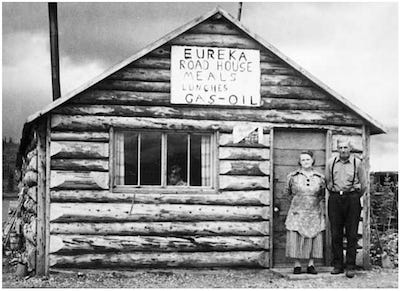

The community of Kantishna was founded as a gold mining camp in 1905, and like many such camps, was originally called by the popular goldrush name “Eureka.” On the north side of Mt. McKinley, with an elevation of 1,696 feet, Kantishna was three miles northwest of scenic Wonder Lake. With the discovery of gold in the area in 1904 several such camps sprouted, but the settlement which became known as Kantishna was located closest to the gold-producing creeks. As the nearby gold camps were abandoned, those who stayed in the area migrated to Kantishna, and a post office by that name was established in 1905, officially stamping the name of the community. In 1909, a land recording office was established, with local miner Bill Lloyd serving as the first commissioner of Kantishna. In 1919 U.S. Geological Survey geologist Stephen R. Capps reported “since 1906 the population of the Kantishna district has remained nearly stationary, ranging from 30 to 50.”

In 1919-20, C. Herbert Wilson became Kantishna’s commissioner, and he constructed the two-story log building which would become the Kantishna roadhouse as a residence for his family. Over the years, the large structure became a focal point of the community, serving as the post office, commissioner’s office, a community gathering spot and a place for travelers to spend the night. The historic Kantishna Roadhouse still stands on its original site, while the modern facility and popular tourist destination of the same name is nearby.

Alaskan roadhouses played an important role in early transportation routes, but time and the harsh elements of the north have destroyed most of them. What remains today is only a glimpse of the great network of roadhouses which once crossed the land, providing food, shelter, and a brief respite from the trail to the hardy travelers who took comfort within their walls. ~•~

Excerpts from the book Alaskan Roadhouses, Shelter Food and Lodging Along Alaska’s Roads and Trails, by Helen Hegener (Northern Light Media, 2015).