The 1935 Matanuska Colony Project

Part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s optimistically grandiose New Deal

“If the government is going to set up colonies all over the country, why not one for Alaska?” Colonel Otto F. Ohlson

Alaska’s dramatically beautiful Matanuska Valley sits at the head of Knik Arm, crossed by two major rivers and surrounded by towering mountains on three sides. Today it is the state’s agricultural heartland, the ongoing legacy of the 1935 Matanuska Colony Project.

The picturesque farms with their soaring-roofed Colony barns are historic landmarks, and reminders of an all-but-forgotten chapter in American history, when the U.S. government rolled the dice and offered 204 Depression-distraught families an opportunity to begin their lives over again, with government financing and support, in this wild northern land.

The Matanuska Colony Project was part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s optimistically grandiose New Deal, a series of economic programs designed to provide the “3 R’s”: Relief, Recovery, and Reform.” Relief for the poor and the unemployed, Recovery of the economy to normal levels, and Reform of the financial system to prevent a repeat depression.

It was an era of outlandish programs dreamed up by bold visionaries, but none were bolder or more outlandish than the government’s rural rehabilitation and resettlement projects, which included Dyess Colony, Arkansas; Arthurdale, West Virginia; the Phoenix Homesteads in Arizona; and similar colonies in over a dozen other states, and the Territory of Alaska.

On April 23, 1935, the Bureau of Indian Affairs ship North Star, chartered from the Department of the Interior by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, left San Francisco bound for Seward, Alaska. On board was a large contingent of administrators, staff, and construction supervisors charged with laying the groundwork for the Matanuska Colony Project.

General Manager Don Irwin, Director of Construction Col. Frank Bliss, his staff, and many others, including an architect, an engineer, a physician and many more who would play key roles in the government’s bold New Deal experiment in Alaska, were transporting the tents, stoves, trucks, tractors, well-drilling equipment and other materials necessary for creating a new community in the Alaskan wilderness.

Also on board were 118 transient workmen, the first group of several hundred who would be building the homes, barns, administrative buildings and roads for the new colony.

Joining this advance guard as the official photographer was an earnest young graduate from the University of California at Berkeley named Willis Taubert Geisman. His thorough documentation of the project was a monumental achievement, and has become the single most frequently referenced work on that uniquely important part of Alaska's history. Over the decades his compelling and beautiful photographs of the Matanuska Colony have appeared in hundreds of books, magazines, news articles, on television, and in films.

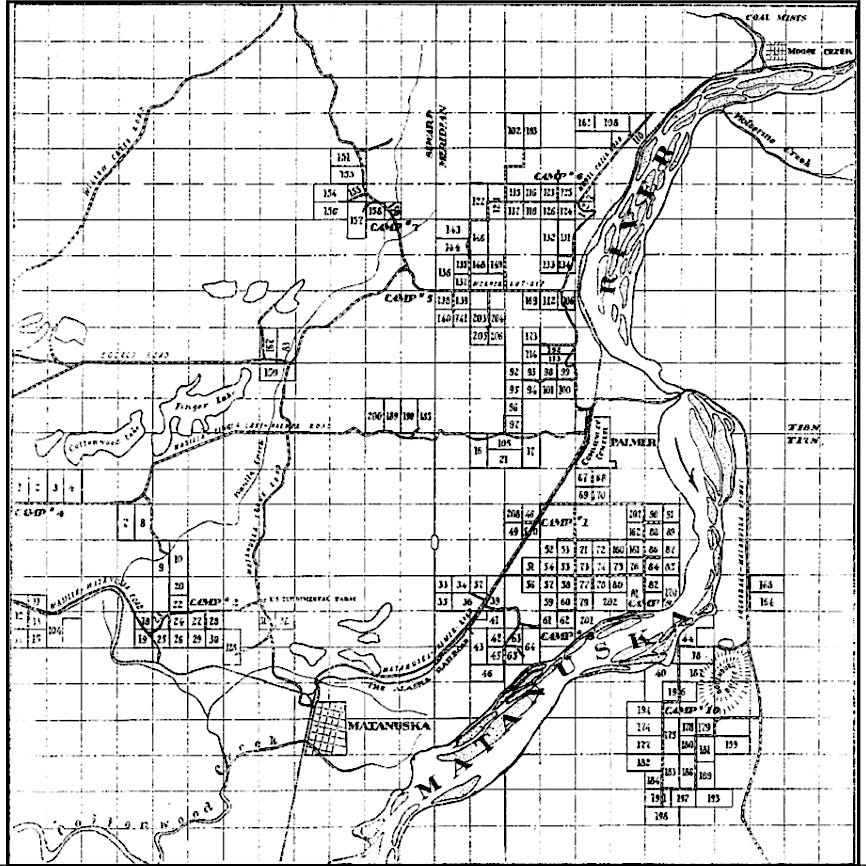

On February 4, 1935, President Roosevelt, by Executive Order, withdrew 8,000 acres in the Matanuska Valley from homestead entry, along the lower reaches of the Matanuska River in the eastern part of the Valley. Framed on three sides by the towering Chugach and Talkeetna mountain ranges, open to the west with a view toward Denali, and bounded along its southern edge by the glacial Knik River, the mighty Matanuska River enters the northeastern corner of the Valley and empties into Knik Arm in close proximity to the Knik River.

Farming in Alaska had been proven feasible by the U.S. government’s territory-wide cadre of agricultural experiment stations, including one near Matanuska. There was no highway from the Valley to Anchorage; weekly passenger and freight train service provided the only mechanical means of travel in or out of the Valley. Palmer, then known as Warton, was only a railroad siding on the branch line to the Jonesville coal mines at Sutton and Chickaloon. There was a freight warehouse and a post office, and a handful of nearby homesteaders.

The town of Matanuska, at the junction of the main railroad line and the spur line to the coalfields, had been created when the government railroad held an auction of townsite lots in 1916. The government built a railroad depot and a freight warehouse at the site, and a small town took shape around them, with a general store, a liquor store, a roadhouse, a post office, a grade school and a high school, and a dance and meeting hall. The name of the town, later applied to the Colony, came from an old Russian translation of a term for the ‘Copper River People,’ who used the mountainous Matanuska River corridor between the Valley and their homeland in the Copper River Basin.

There were already many farms in the area. In Matanuska Valley Memoir, Bulletin #18 from the Alaska Experiment Station, July, 1955, authors Hugh A. Johnson and Keith L. Stanton describe early farming development:

“Agriculture in the Valley came into its own in 1915. Most of the 150 settlers filing for homesteads came intending to farm. Some cleared enough land to put in a crop the next year. Settlement was concentrated in the vicinity of Knik, across the Hay Flats and up the Matanuska River with a few homesteads spotted along the trails leading to Fishhook Creek. The greatest influx of settlers occurred in 1916 and 1917. By the end of that period nearly all the available land had been homesteaded--a fact not commonly known.”

In her classic Old Times on Upper Cook’s Inlet, author Louise Potter printed a list of 132 people who had homesteads near Knik in 1915, noting, “That such a list is possible at all is apt to come as a surprise to many who have been encouraged to believe that 1935, the date the ’Colonists’ arrived in the Matanuska Valley, marks the beginning of the history of agriculture in the Upper Inlet Region...”

It was the Colonists’ good fortune to land in a dramatically beautiful Valley which already had a rich agricultural history, for Alaska had been advertised and promoted to farmers for many years before the Colonists headed north.

Arville Schaleben was a cub reporter working for The Milwaukee Journal in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when he was presented with the opportunity of a lifetime. The newspaper offered to send the young journalist to Alaska with the Matanuska colonists in return for a series of articles about the government's unusual New Deal experiment.

Schaleben leapt at the offer and travelled to Alaska with the Wisconsin families, living alongside them in the Palmer tent city that first summer, writing and filing stories almost daily - over 150 stories and more than 400 photographs - which appeared in The Milwaukee Journal and were also syndicated in newspapers around the country. The resulting series of articles was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cemented Schaleben’s reputation as a journalist.

Historic photographs show parallel rows of neat white cabin-style tents built for the colonist families, and inside each tent was a new coal- and wood-burning cookstove, already burning to warm the tent inside and with a bucket of coal alongside for stoking throughout the night. Simple beds with springs, mattresses, sheets, and blankets awaited the tired colonists, and each tent was stocked with food and the basic necessities. Original plans for the colony had called for all of the families to remain in the central tent city while their homes were being constructed, but that plan changed, and they were split up into eight different camps, to enable each household to be near their own farms while the land was being cleared and permanent homes built.

On May 23 the drawing for farm tracts was held, the majority were 40 acres in area, but some tracts contained as much as 80 acres. With their tract locations determined the colonists were moved into the tent camps closest to their new farms, some close in to Palmer and others several miles away, including some closer to the railroad town of Wasilla and a large group across the Matanuska River at Bodenburg Butte.

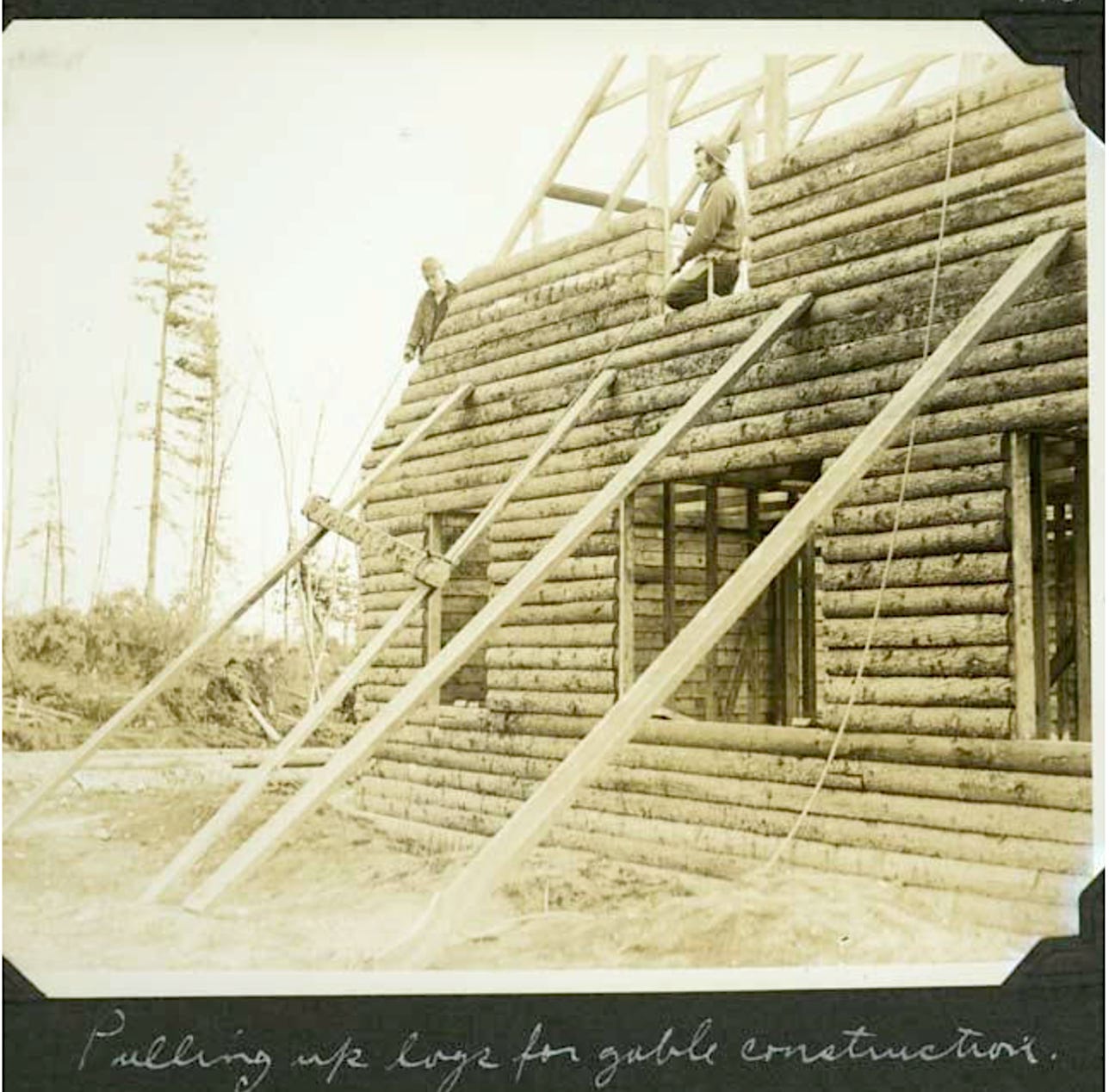

Life in the tent camps during the first few weeks was challenging, with firewood and water to haul, and deep mud from the cold and rainy weather, but the families made do, knowing their homes were being built and the tent camp situation was only temporary. Five plans for houses were offered to the colonists, each a single-family “rustic cottage” design developed by the FERA architects in Washington, D.C., working under David R. Williams. Most of the homes, which ranged in size from 900 to 1,500 square feet, were one-and-one-half story with rectangular or L-shaped floor plans, although a few were single-story homes. Constructed of log, frame, or a combination of both, the houses featured gable roofs; four of the designs were three-bedrooms with a combination kitchen and living room, storage room, and many built-in elements; the fifth was a similar four-bedroom design. None of the homes included indoor plumbing or bathrooms, but there were spaces for the future development of indoor bathrooms. Likewise, none of the original plans had a full basement, but some of the colonists elected to dig their own basements after the fact.

The barns built for the colonists’ farms were of a standard design, 32’ by 32’ by 32’ high, recommended to support a subsistence family farmstead as originally intended by the government planners. Other outbuildings included chicken coops, well houses, sheds, and of course, outhouses. Wells were driven to supply each farm with an adequate source of water.

The cost of the homes and farm buildings was reported in the 1950 study for the U. S. Department of the Interior by Kirk H. Stone, titled Alaskan Group Settlement: The Matanuska Valley Colony: “Homes, barns, and wells cost more than was anticipated... The estimates in March, 1935 were $1100 for a home and well and $200 for a barn. These figures were revised in May to: $985 per house, 50 barns at $598 each, and material for 150 barns at $200 each, and $140 per well. Actually, the appraised costs in May, 1936 averaged: $1830 per dwelling, $506 for each barn, and $511 per well. The estimate on the barns was the only building cost anticipated accurately, but the barns were the buildings considered least suitable by the colonists.”

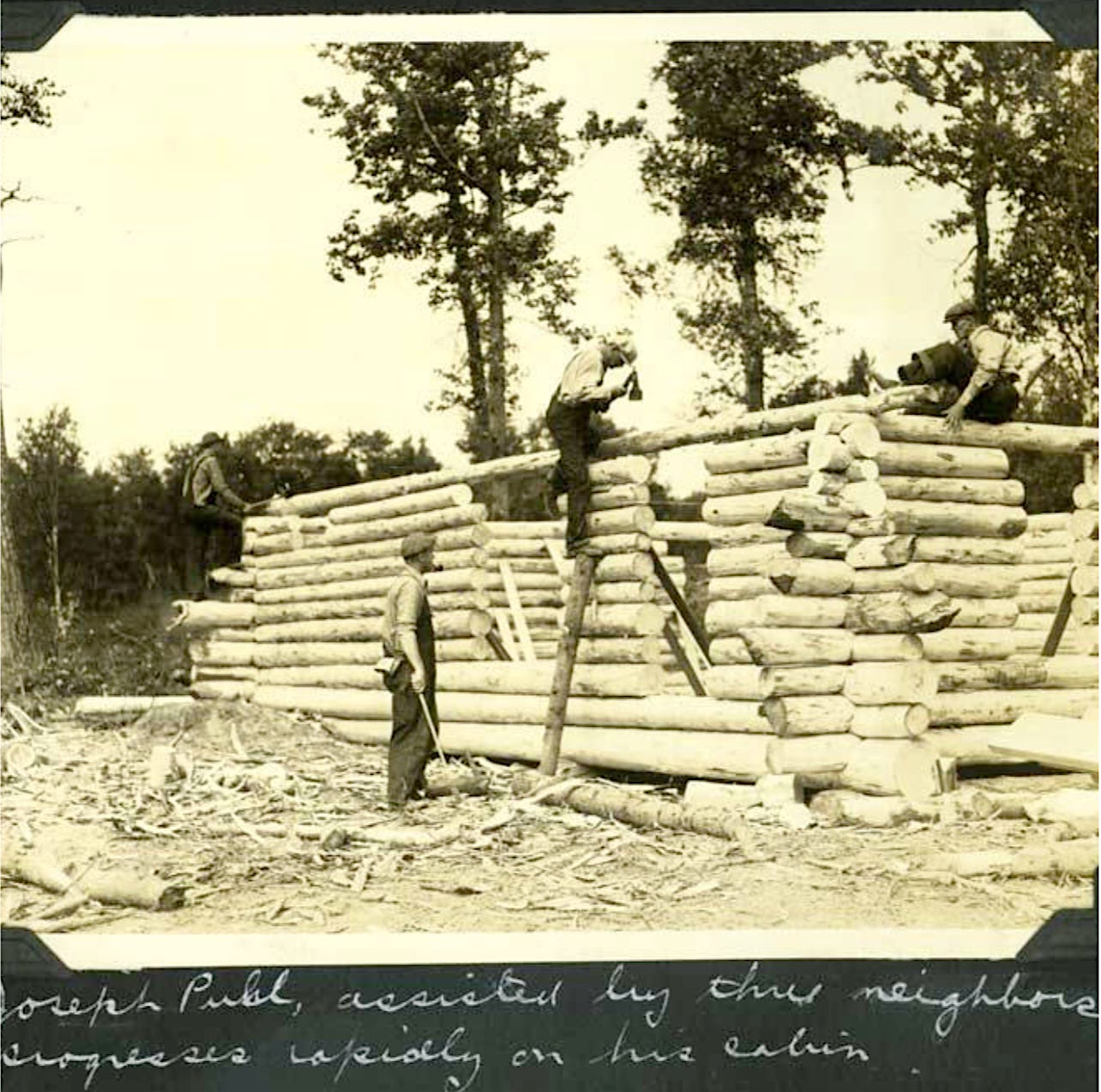

The colonists’ camps were vibrant places where dozens of children and dogs raced and played as the women shared recipes along with the latest news from other camps. The men formed crews to cut logs for their homes and barns while developing croplands and pasture. They fished in the streams, and talked and played endless card games in the evenings. Through shared hardships and hard work, community meetings, church services, and events such as dances in neighboring towns, the intrepid families who left their stateside homes and ventured north to Alaska were slowly building a new life.

The A.R.R.C. General Manager Don Irwin was liked and appreciated by the colonist families. He was an understanding and patient man, a hard worker, a fair administrator, and a very keen observer. A case in point was Irwin’s descriptive appraisal of the Milwaukee Journal reporter, Arville Schaleben, in his later book, The Colorful Matanuska Valley:

“He felt that this project rated something more than a few days of exciting, inflammatory headlines. He dug deeply into what was going on. He was not afraid to walk, thumb a ride on a Corporation truck, or borrow a horse from a Colonist to ride, if he could get the exact information he needed for his reports. It was not at all unusual to see Schaleben riding a horse bareback, at a lope, coattails, elbows, dispatch case and camera flying, hurrying to the railroad depot to file a deadline report for his paper. He was with the colony for four months. It is certain that the more conservative press in the South 48 states depended a great deal on information supplied by Schaleben through his Milwaukee Journal reports.”

Throughout the summer of 1935, Arville Schaleben kept the Matanuska Colony in the headlines of The Milwaukee Journal, but he also devoted many columns of newsprint to sharing stories of the mundane, day-to-day lives of the Colony settlers. He wrote about the housewives tending their chores, the children playing games, a colonist being chased by a black bear, the workers building the homes, events in the community, the officials, the land, and even the weather. He punctuated his stories with photographs which added a visual dimension, with striking images of life in the Alaskan colony such as neat white tents in a row, transient workers heaving logs into place for a colonist's cabin, children playing marbles in the dirt, and scenes from the first funeral held by the colonists, for little Donald Henry Koenen. At the tender age of four he had died of “heart trouble, possibly aggravated by two weeks of measles.” Schaleben shared details of the child’s burial “...in a homemade wooden casket covered with wild roses and bluebells that his playmates had gathered.”

On Thursday, August 13, 1935, a short item ran at the top of the front page of The Milwaukee Journal, bylined “By Special Cable to the Journal” and signed by Will Rogers, famous actor, author, humorist and social commentator, who had been contributing to the newspaper for nine years. Titled “Nothing to Do, So He Flies Over Peak,” the article shared the travels of Rogers and his friend and pilot, Wiley Post, who were en route to Siberia for a holiday of hunting and fishing. At the bottom of the same front page, Arville Schaleben wrote about the popular humorist’s visit to the colony, after which Rogers commented, “The valley looks great. It looks fine, fine. You got a mighty nice place here..”

The next morning Milwaukee Journal readers were startled to see a large quarter-page photo of Will Rogers and Wiley Post standing beside Post’s airplane, under a bold black page-wide headline which read “Crash Kills Will Rogers, Post.”

The beloved humorist and the flier who had circled the world had crashed on their way to Point Barrow. Rogers was mourned world-wide, and his presence, which had brought laughter and renewed hope at a time when the nation most needed it, would be greatly missed by the American public. His lasting tribute to the Matanuska Colony was a one-liner in his final dispatch which mused, “There’s a whole lot of difference in mining for gold and mining for spinach!”

Throughout the late summer and early fall of 1935 the colonist families continued to work on their farmsteads, and from the vantage point of thirty-three years later, Don Irwin summed up the situation: “The summer was over. The efforts of the construction crews had produced excellent results. The families and livestock were under roof. There was a lot to be done by the individual families to finish the interior of their homes, but life seemed not so tense and the prospects looked much brighter even though their personal indebtedness was mounting.”

The indebtedness of the colonist farmers was a source of contention, to be sure, but an article by colonist wife Klaria Johnson, who had traveled to Alaska from Wisconsin with her husband, Victor, portrayed an exuberant joy in her newfound home: “‘Martyrs’ with their lurid stories of danger, hardship, and injustice aroused more concern than the quiet, patient, pioneering-minded people who expected to put up with the bitter and the sweet. We colonists weren’t really having a bad time. We went about building our home without the help of corporation carpenters–four neighbors went together. Each day I walked out to our tract and cooked lunch for the workers on a campfire under the birches. The fragrance of new-cut timber and moist earth, mingling with the good smells of coffee and frying bacon, will always be to me symbolic of those busy days of home-building and the high hope that was in us. Four months after landing in Palmer, we moved into our new house.”

Although fraught with inevitable bureaucratic entanglements, frustrating delays, personality clashes and a myriad of other distractions, the Matanuska Colony actually thrived for the most part, and the majority of the families remained to raise their families and make their permanent homes in Alaska. Highways were built, the wide Matanuska and Knik Rivers were bridged, and the town of Palmer became the center of commerce and society in the Valley. By 1948, production from the Colony Project farms provided over half of the total Alaskan agricultural products sold.

Today the Matanuska Valley draws worldwide attention for its colorful agricultural heritage and its uniquely orchestrated history. The iconic Colony barn, often seen around the Valley now in artwork, logos, advertising and other uses, has become a beloved symbol of this unique chapter in Alaska’s history. ~•~

Excerpted from “A Mighty Nice Place,” The History of the 1935 Matanuska Colony Project, by Helen Hegener (Northern Light Media, 2016). See Sources & Resources on page 48 for more information.