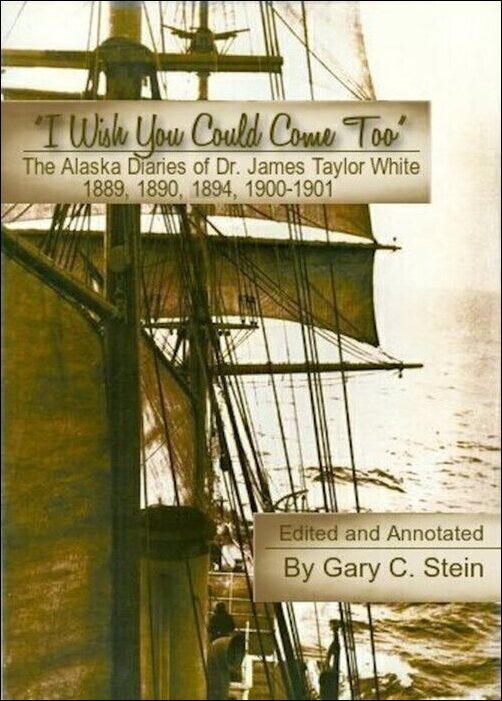

“I Wish You Could Come Too,” The Alaska Diaries of Dr. James Taylor White, by Gary C. Stein, published in November, 2021 by Northern Light Media, is a first-hand look at life aboard a revenue cutter during Alaska’s formative early years. The ships of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Revenue-Cutter Service patrolled the waters of the Bering Sea, the coast of Alaska, and the Yukon River, and for several of those voyages a bright and engaging young physician, Dr. James Taylor White, served aboard and recorded his adventurous work in personal correspondence and journals. Dr. Stein’s book is the result of four decades of research; heavily annotated, indexed, and with an extensive bibliography. Available at Amazon or from the publisher.

Prologue to the Cruise of 1889

[Notes have been deleted from this excerpt.]

On February 15, 1889, Dr. James Taylor White wrote to Captain Michael A. Healy, commanding officer of the U.S. Revenue Steamer Bear, requesting appointment as surgeon for the cutter’s upcoming cruise to Alaska. White enclosed two recommendations from former professors in the Medical Department at the University of California. Dr. W. E. Taylor, Professor of Practical Surgery, wrote that White was “a competent physician and a gentleman.” The other reference, Dr. W. Beverly Cole, President of the Medical Faculty, stated that White, “having pursued a 3 years course of instruction & passed a satisfactory examination, & being of good moral character,” was “in every way competent to act as surgeon of a Revenue Cutter.”

White did not include a better reference; it was unnecessary. His father was well known to Revenue-Cutter Service officials on both the east and west coasts, and in forwarding the doctor’s request to the Secretary of the Treasury Captain Healy stated that as Dr. White was the son of Captain John W. White he “would be very acceptable.”

It took more than two months for the Treasury Department to respond. On April 26, Assistant Secretary George C. Tichenor finally authorized White’s employment as surgeon. White’s duties as the Bear’s medical officer would begin on May 1 and continue until the cutter returned to San Francisco after its Arctic cruise. He was twenty-two years old. A later passport application described him as 5’7” tall with blue eyes, brown hair, a medium forehead, proportioned nose, small mouth, fair complexion, and an oval face (see frontispiece).

Elated at the prospect of going north, White jokingly told his grandfather, Colonel James Taylor, that his early duties on board “are about as hard as I have ever had, especially trying to find something to do. When I first came I had to examine the crew physically, and since then I have had three or four sick. Besides this the making out of my requisition for medicines and the attending to the filling of the same has constituted the arduous duty imposed on me for the month of May for which I get $150.00 and $.30 per day rations. I think as the saying goes I have a pretty fat job.”

White explained to his grandfather that the Bear was taking on board lumber and provisions to build a whalemen’s refuge station at Point Barrow. Ships venturing north through Bering Strait, whether revenue cutters, trading vessels, or the whaling fleet, had to contend with an ominous natural force—the Arctic ice pack. For years the American whaling industry tried to convince Congress that a government station was needed in the Arctic to provide shelter and sustenance to shipwrecked whalemen. In 1848 Thomas Roys took his whaler Superior north of Bering Strait for the first whaling venture in the western Arctic. Three years later, when 145 ships comprised the Arctic fleet, startling news of shipwrecks reached Washington. At first there were few details, but it was soon learned that “the losses during the year 1851 have been unprecedented. ... No less than seven sail of this fine fleet ... have been wrecked there and left behind as monuments of the dangers which meet these hardy mariners in their adventurous calling. There are reports of other losses and wrecks.”

There were more losses during the Civil War when the Confederate raider Shenandoah captured twenty-four whalers and sank another twenty near Bering Strait. Disasters continued to haunt the fleet in the 1870s, even as the number of vessels in the Arctic fleet shrank and profits from their voyages began a steady decline. Thirty-two whaling ships of a fleet of sixty-one were crushed in the ice southwest of Point Barrow in 1871. More than 1,200 persons on board, including some of the officers’ wives and children, were miraculously saved and brought to Hawaii by seven whalers that had luckily removed beyond the edge of the ice pack. The loss to the whaling industry was staggering, ranging from $1,600,000.00 to $2,500,000.00 ($35,000,000.00 to $54,600,000.00 in 2020 dollars). Another twelve whalers were lost in the ice in 1876. The whaling fleet numbered only twenty ships that year, so the loss of twelve was as significant ($817,000.00, or $20,400,000.00 in 2020 dollars) to the industry as the loss of thirty-two in 1871. Insurance rates tripled after these disasters.

The catalyst came in 1888 when Arctic wind and ice wrecked the Jane Gray, Young Phoenix, Fleetwing, Mary and Susan, and Ino. Voicing his opinion as “to the great importance of establishing a Life-Saving Station at Point Barrow,” Lieutenant Commander William H. Emory of the U.S.S. Thetis wrote the Secretary of the Navy that “were it not for the accidental visit of the ‘Thetis’ or the ‘Bear’, there might be great loss of life at this point, and the wrecked men would be left without sustenance.” At last moved to assist an industry “representing a capital of over $2,000,000 and furnishing employment to from twelve to fifteen hundred seamen annually,” Congress appropriated $15,000.00 to construct and provision a station near Point Barrow. The Treasury Department authorized the Bear to carry the precut lumber for the building and its supplies north, along with the station’s superintendent, Gilbert Bennett Borden. The project has been rightly characterized as “planned hurriedly, staffed expediently, and closed prematurely.”

Gathering building materials and supplies between Congress’s appropriation for the project on March 9, 1889, and the Bear’s sailing in June was an impressive feat of government contracting. Captain Healy did not receive orders from the Treasury Department to “procure in open market immediately proposals for house, outfits and provisions” until May 3. Within a week, Healy telegraphed back that bids were received for the house and provisions despite the short time span making it difficult to obtain bids. Besides the forty tons of coal and estimated forty-five tons of building materials for the station itself there were thousands of pounds of supplies: food, tools and hardware; stoves, kitchen equipment, dinnerware and utensils; firearms and ammunition; bedding and furniture; medicines and medical supplies; trade goods and a completely equipped whaleboat. The total expenditure for 1889, including salaries for the superintendent and assistants, was slightly less than the amount appropriated—only $13,202.38.

White felt slightly wary about the cruise. Captain Healy and his Executive Officer, 1st Lieutenant Albert Buhner, had reputations for being hard men to please. White told his grandfather that “if I can manage to get along with the Captain and 1st Lieut (which is doubtful) I will have a delightful cruise. However I will do my best, as since others have gone up there with these officers and have returned alive, I think I can.” White’s concern about Healy was almost prophetic, but no one on the Bear would face more consequences for the captain’s actions during the 1889 cruise than “Hell Roaring Mike” Healy himself.

The steam barkentine Bear was not the only revenue cutter to see extensive service in the Arctic, but it was certainly the most famous. Built in Scotland in 1874 for sealing, the U.S. Navy purchased the vessel in 1885 to assist in the search for Lieutenant A. W. Greely’s missing Arctic expedition. Captain John. W. White had advocated for the presence of revenue cutters in Alaskan waters after his cruises in the 1860s and 1870s, but cutters assigned to this duty were not, as the secretary of the treasury wrote in 1878, “designed originally for such long voyages as this work requires and are not well adapted to this cruising.” The secretary continually had trouble convincing Congress to set an appropriation for more adequate vessels. In 1884, for example, although the cutter Corwin was performing well, the secretary wrote that Congress’s “attention is invited to the recommendations of five former reports that a vessel be provided for duty in Alaskan waters.” Not getting quite what he wanted—a new vessel—the secretary was nonetheless pleased that same year when Congress authorized the Bear’s transfer to the Revenue-Cutter Service.

In 1885 the Bear was refitted and sent to San Francisco, where Captain Healy took command for its first Alaskan cruise in 1886. One Coast Guard historian has written that the Bear “is a symbol for all the service represents—for steadfastness, for courage, and for constant readiness to help men and vessels in distress,” and Healy was consistently praised as having the same qualities (Figs. 2 and 3).

Captain Healy was an acclaimed Arctic hero. Just the year before, in 1888, he brought 108 shipwrecked whalemen to San Francisco after the whaling fleet disaster that year. Letters and resolutions subsequently flooded the Treasury Department from the whaling industry attesting to Healy being “an able and fearless officer, the right man in the right place at every critical time.” It was probably because of Healy’s popularity as much as for his skills as an Arctic navigator that he and the Bear were chosen to transport and construct the Refuge Station.

Successful completion of the Refuge Station added more glory to Captain Healy’s reputation in 1889, and after the Bear returned from its Arctic cruise the whaling industry presented him with a testimonial extolling his diligent “protection and care of this adventurous and valuable industry.” A month later, however, a mass meeting sponsored by the Coast Seaman’s Union and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union labeled Healy a “disgrace to the service” and a “demon” who, while intoxicated, had tortured sailors at Unalaska in June 1889. Healy would face these charges before a Treasury Department board of inquiry in 1890. He was eventually found justified in his treatment of the sailors. The more serious charge of drunkenness was determined “wholly unsustained.”

Dr. White, however, was not called to testify before the board. As his diary of the Bear’s 1889 cruise shows, if he had been called the outcome for Healy might have been quite different.

“I Wish You Could Come Too,” The Alaska Diaries of Dr. James Taylor White, by Gary C. Stein, published in November, 2021 by Northern Light Media. $29.95 plus $6.00 shipping. 412 pages, over 45 photographs, images, and maps. 6″ x 9″ b/w format, extensively annotated, bibliography, indexed. Available at Amazon or from the publisher, Northern Light Media.