Northern Light Media, publisher of Alaskan History Magazine, published The Beautiful Matanuska Valley in 2014, with stories and full color photos of Palmer, Wasilla, Knik, Sutton, Matanuska, Big Lake, Chickaloon and other communities in the area bounded by the Chugach and Talkeetna mountains and the Knik Arm. These stories tell of the founding, settling, and development of the Valley, while details about the geography, geology, transportation, agriculture, mining, recreation, tourism, and history – highlighted by hundreds of full-color photographs – showcase the many wonders of the beautiful Matanuska Valley.

“This valley is just a little piece of heaven. Everything I ever hoped to find is here.” James Landehorne, 1948 [Northern Light Media photo]

Matanuska Valley Maps

The earliest maps of the Matanuska Valley were undoubtedly drawn in the dirt with a stick, as a hunter described where he saw a moose or a fisherman explained where he caught a brightly shining salmon. Later maps may have been drawn on the tanned hides of animals, and much later there were sketchings on paper leading to the gold discoveries and routes to and from the sparse settlements of pioneers.

Today the Matanuska Valley is filled with maps showing details of history, geography, geology, and more, and up-to-date printed maps are readily available at the many visitor centers scattered throughout the Valley. Maps are even found online via computer or cellphone; simply search for the name of a location or a landmark and a profusion of excellent maps will appear, with descriptions and photographs and helpful reviews of whatever local attractions can be found in the vicinity.

Palmer Hay Flats

Farmers who homesteaded the Matanuska Valley in the early years of the nineteenth century found natural grazing lands for their cattle, sheep, and horses in the flat lands between the last wooded bluffs and the channels of Knik Arm. Dubbed the Palmer Hay Flats, these wide open pastures were a welcome sight to the later farmers who arrived with the 1935 Matanuska Colony Project with cattle and horses to feed.

Good Friday Earthquake

On March 27th, 1964, a 9.2 earthquake changed the nature of the Palmer Hay Flats forever, lowering the ground by a couple of feet in some areas, much more in others. What had been dry pasture-like hayfields became marshy swampland, and skeletal ghost forests, a result of the subsidence of the land which occurred during the Good Friday earthquake, still stand in many areas. Today the former grazing lands are a birder’s paradise, hosting thousands of migratory waterfowl each year.

Palmer Hay Flats Game Refuge

The vast expanse of the Palmer Hay Flats State Game Refuge, one of six refuges managed by the Palmer Fish and Game office, is a unique and increasingly accessible place, with trails for wildlife viewing and shelters for family gatherings. The Cottonwood Creek and Reflections Lake sites are the first to be developed, with trails and facilities for visitors. Community outreach events and programs connect people with the land through recreation and education, and eventually a year round nature, science, and public use facility will be available for learning about the wonders of wetland ecosystems, migrating birds, and the seasonal ebb and flow of wildlife.

Eklutna Power Plants

Early Electrification of Anchorage

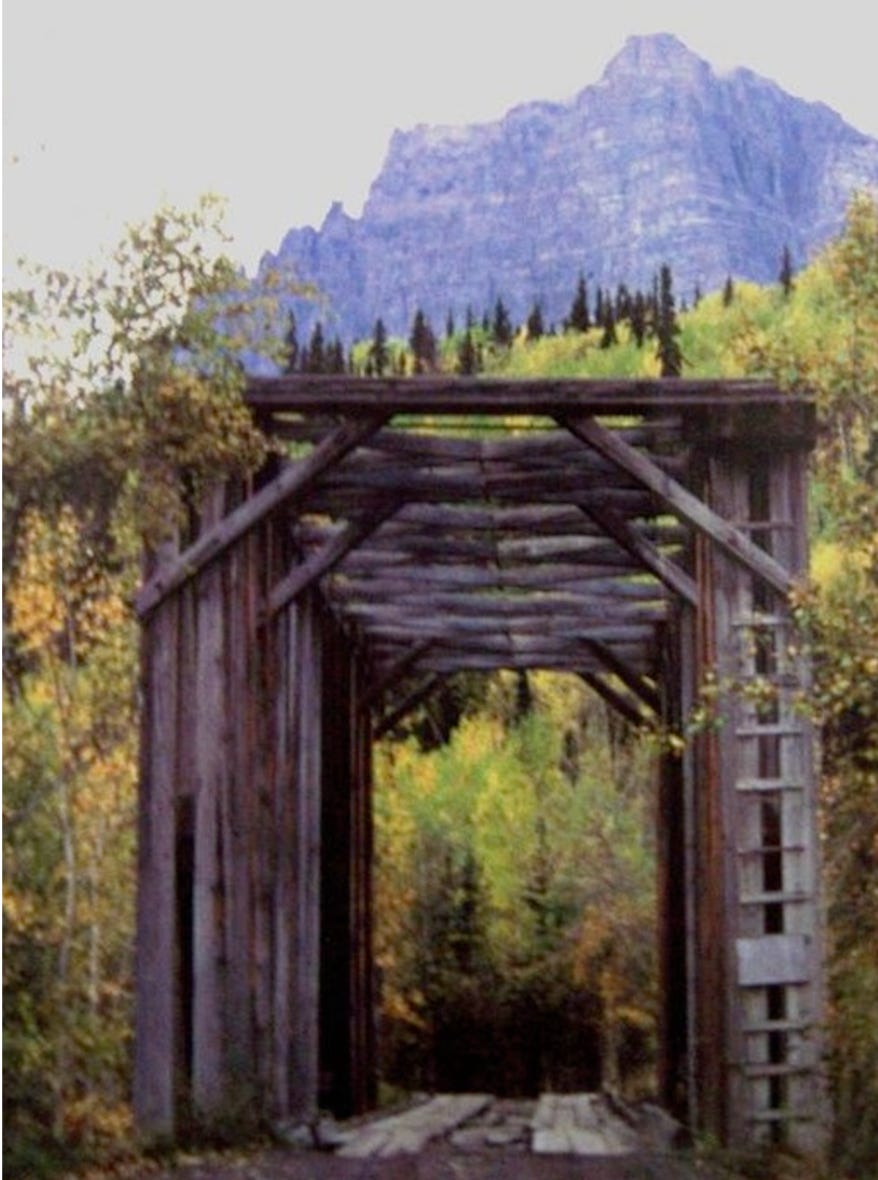

Frank I. Reed founded the Anchorage Light & Power Company in 1923 and developed the Eklutna Power Plant, harnessing the power of the Eklutna River in 1929. A concrete arch dam, 98 feet long and 61 feet high, diverted water from the Eklutna River and into an 1,800 foot tunnel through Goat Mountain, to the concrete powerhouse. The Old Eklutna Power Plant provided 2,000 kW of power, during which time the city grew from a small railroad settlement into the largest city in Alaska. In an era dominated by federal projects, Frank Reed built an independent power company which supplied the city of Anchorage for over 25 years. Reed sold his power plant to the city for $1,000,000 in 1943. When the New Eklutna Power Project was authorized in 1950, the old Eklutna plant was shut down and the dam allowed to fill with silt and gravel. The powerhouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The New Eklutna Power Project

The New Eklutna Power Project, funded and built by the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation, was built several miles upriver from the old power plant. A 4.5 mile long tunnel was bored through East Twin Peak to provide water for the New Eklutna Power Plant. Drilling the nine foot diameter tunnel from both the Knik River side and the Eklutna Lake side began in 1951 and connected in October, 1953 - a marvelous engineering feat for its day. The Eklutna Project was dedicated on August 29, 1955, providing a 33,000 kW capacity to the city of Anchorage, the military bases of Fort Richardson and Elmendorf, and communities in the Matanuska- Susitna Borough.

Chickaloon

The Ahtna name for Chickaloon Native Village is Nay’dini’aa Na,' which means “the river with the two logs across it.” The Ahtna Athabascan Tribe has occupied one of the most picturesque areas in Southcentral Alaska for 10,000 years, but as the traditional lands were subjected to mining, logging, and oil and gas drilling, the introduction of alcohol and diseases such as polio, tuberculosis, and the Spanish Influenza, brought in with development, almost wiped out the Tribe.

During the 1930s-1950s, a mandatory education system intended to assimilate Alaska Natives, established and enforced by the United States government, removed many children from their families and placed them in boarding schools throughout the state. Yet through it all, the Chickaloon Tribe has endured. With the passing of the Alaska Native Claims and Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971, Tribal Elders re-established the Chickaloon Village Traditional Council (CVTC) in 1973, to reassert the Tribe’s identity, cultural traditions, economic self-sufficiency and to reunify its citizens.

The Colony House Museum

The Colony House Museum, located in the historic district of Palmer at 316 E. Elmwood Avenue, features the Colony home once owned by Irene and Oscar Beylund. The Beylund home traces its history back to the 1935 Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal Matanuska Colony Project resettlement program.

The Beylunds were from Wisconsin, and they drew tract number 94, which was located on Scott Road, northwest of Palmer, with a stellar view of the mountains. Of the five house plans available to the Colonists, they selected this classic frame house design. The house was restored by a group known as the Colony House Preservation Project Committee, organized in 1994 for the purpose of restoring a house from the Colony era to it’s 1936-1945 appearance. In 1998 the project was turned over to Palmer Historical Society, who currently operate it as a museum. The house, its furnishings, and the adjacent outbuildings display rural life in the Matanuska Valley during the heyday of the Colony.

Another free book excerpt from Northern Light Media.