This is an excerpt from Alaska and The Klondike: Early Writings and Historic Photographs, an anthology of selected writings by early explorers and travelers in Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada. Compiled and edited by Helen Hegener and published by Northern Light Media in 2018.

Selected excerpts from

THE LAND OF NOME

A NARRATIVE SKETCH OF THE RUSH TO OUR BERING SEA GOLD-FIELDS, THE COUNTRY, ITS MINES

AND ITS PEOPLE, AND THE HISTORY OF A GREAT CONSPIRACY 1900–1901

by

Lanier McKee

Published by The Grafton Press, New York, 1902

Preface

After returning from his first experience in Alaska in 1900, the author was prompted to write from his diary, primarily for his friends, a sketch of the rush to the Cape Nome gold-fields and the character of the country and its people. This account, with some modifications, forms the first half of this book. The second half, parts of which were written in the atmosphere of the situations as they arose during the following year, has been recently completed upon the adjudication of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Pacific Coast, which, in effect, finally frees northwestern Alaska from one of the most dramatic and oppressive conspiracies in recent history.

The writer believes that the discovery of this El Dorado of Bering Sea has created an epoch in the development of our national domain, wonderful and unprecedented in various phases, and but little understood or appreciated by the general public. Because of its uniqueness, it is a difficult matter to treat adequately. Certain features of the subject can hardly be exaggerated; for instance: the magnitude and blindness of the stampede of eighteen thousand fortune-hunters in the summer of 1900, and the almost indescribable scenes which attended their arrival on the "golden sands"; the marvelous richness of some of the placer-gold deposits; the dreariness and barrenness of the new country; and the enormity of the judicial conspiracy, whose proceedings the United States Circuit Court of Appeals has declared "have no parallel in the jurisprudence of this country."

Special laws concerning Alaska, the local methods of mining, and various other matters pertaining to the country and its people, are dealt with herein, probably with sufficient fullness for the general reader. The book, however, as a whole, is in narrative form; and personal experiences and character-sketches (especially in the second part) have been freely utilized for the purpose of illustrating characteristic conditions and typical people.

If the narrative in places seems too personal, this, perhaps, will be pardoned, for the reason that an account of the actual experiences of a few individuals—tame, indeed, compared with those of many others—may better suggest the atmosphere of a weird land than a mere résumé of impersonal facts. Finally, it is hoped that this book may, in some small measure, prove of service in directing attention to the past neglect and present needs of our wonderful Alaska.

New York, February, 1902.

From Chapter 1: The Rush in 1900

Remarkable discoveries of gold at Cape Nome, Alaska, situated almost in the Bering Strait, only one hundred and fifty miles from Siberia, and distant not less than three thousand miles from San Francisco and fifteen hundred from the famed Klondike, naturally created more excitement in the Western and mining sections of this country than in the Middle States and the "effete East," an expression frequently heard in the West. These rich placer-gold deposits were discovered by a small party of prospectors in the late autumn of 1898. The news spread like wild-fire down along the Pacific coast and up into Dawson and the Klondike country, and the following spring witnessed a stampede to the new El Dorado, which, however, was wholly eclipsed by the unprecedented mad rush of eighteen thousand persons in the spring ensuing. During the summer months of 1899, when, in addition to the gold along the creeks, rich deposits, easy to extract, were found in the beach extending for miles by the sea, every one at Nome had an opportunity to share in nature's unexpected gift. Consequently, upon the return in the fall, the story of the wonderful wealth of this weird country was circulated broadcast. All kinds of schemes, honest and dishonest, were devised during the winter to obtain the gold the following season, and the matter of providing suitable laws to meet the many difficult conditions and questions which had already arisen, and which would be greatly aggravated by the threatened and succeeding stampede, came definitely before Congress. Alaska, legally, is not even a Territory, though commonly so called. It is the District of Alaska, possessing a governor and other officers, but, unlike a Territory, no legislature; and it is, therefore, entirely dependent upon Congress for all legislation. The Alaska bill, under the charge of Mr. Warner in the House and Senator Carter in the Senate, consumed a great deal of the time of Congress; many of its provisions were hotly debated, and finally it became a law, June 6, 1900—in the main a satisfactory piece of legislation. By it Alaska was divided into three judicial divisions, and that which embraces northwestern Alaska and the new gold-fields was allotted to Arthur H. Noyes of Minnesota, formerly of Dakota. If ever a position demanded an honest, able, and fearless man, it was this judgeship, which should be the guaranty of good civil government, establish a court, and disentangle and dispose of, among a mixed population largely composed of unscrupulous elements, an indescribable mass of legal matters, already accumulated and ever increasing.

When in Washington in the winter of 1899, I became interested in Cape Nome. I met there an able young attorney from the Pacific coast, who among the first had gone to Nome, where he had practiced his profession with great success and secured interests in some promising properties. He was then in Washington in the interest of Alaskan legislation. The prospects for great legal complications in the new country were highly encouraging. Lieutenant Jarvis of the United States revenue service, a man of sound judgment and few words, who so signally distinguished himself in 1897 by his overland expedition and rescue of the crews of whaling-vessels ice-bound in the Arctic seas, had been the chief agent of the government at Nome the preceding year. He not only corroborated what I had already heard, but gave the impression that the story had not half been told. My brother and I decided to make the venture, and to be content with a safe return and a fund of experience, to offset the uncertain rewards of business and law practice during the dull summer months. He took up surveying, and I spent all my spare time in studying the elaborate codes of laws which Congress was then enacting for Alaska, as well as substantive mining law and all available information pertaining to that little known or understood country.

In San Francisco there were many signs of the Nome excitement. "Cape Nome Supplies," in large print, met the eye frequently. One ran across many who were going, and heard of many more who had already started for the Arctic gold-fields. All indications pointed to the advent of a small army of lawyers and doctors on the shores of Nome. But, though there was a stir in the atmosphere, the excitement was nothing compared with that at Seattle, which is the natural outfitting-point for Alaska; for San Francisco has had a long experience in these "excitements," and treats each recurring one with comparative indifference. We took everything with us,—tents, stoves, provisions, all sufficient to enable us to live independently for three or four months,—not to mention the "law library" and surveying apparatus.

The C.D. Lane was the ship, named after its owner, the prominent mining man, who had backed up his belief in the genuineness of the new country by investing in it a great deal of money, and who was now taking up in his boat machinery, supplies, miners, and general passengers, some four hundred persons in all. The sailing from San Francisco, and the scenes of farewell at the dock, were both amusing and impressive. Ready exchanges of repartee between the ship and the dock were in order. Passengers held up "pokes," small buckskin bags for gold-dust, and cheerfully shouted to their friends that they would come back with their "sacks" full. But there was about it all at the same time something not altogether gay. It was no certain undertaking. The great majority, of course, would not return successful, and it was not improbable that some might not return at all.

[Not included are details of the voyage via Seattle and Dutch Harbor.]

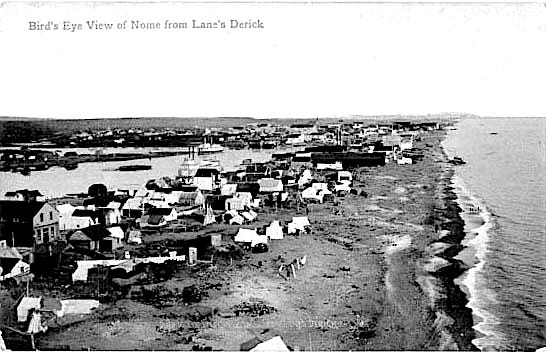

The first sight of Nome City, as we steamed toward the place in the clear morning light of June 20, was impressive. It was indeed a "white city," tents, tents, tents extending along the shore almost as far as the eye could see. Scattered in the denser and more congested part of the town were large frame and galvanized-iron structures, the warehouses and stores of the large companies; and there was the much-talked-of tundra, upon which the multitude were encamped, extending back almost from the edge of the sea three or four miles to the high and rolling hills, which bore an occasional streak of snow. Not a tree, not a bit of foliage, nothing green, was in evidence. Had it not been for the chance discovery of gold in that remote spot, one passing along the coast would have considered it barren and forlorn, "a dreary waste expanding to the skies." There is not even the semblance of a harbor. It is a mere shallow roadstead open to the clear sweep and attack of the Bering Sea. Anchored from one to two miles from the shore were strung along, I may say, scores of nondescript steamers and sailing-craft, with here and there a tug towing ashore lighters filled with passengers or freight, or bringing them back empty. These tugs were so few that they could command almost any price for a day's use, and proved veritable gold- mines to their owners. When the sea is at all rough no disembarking can be done. We were in great good luck to have at that time an unprecedented spell of clear weather and calm seas, which tended to lessen the confusion and misery, which were, even under those favorable conditions, only too great.

Well, here we were finally and at last, and now to face the music! Bundled into scows, passengers were towed by the light-draft boats to within some thirty feet of the shore, and then the scows were allowed to drift in upon the moderate but wetting surf. Women were carried ashore on the backs of men who waded out to the lighters; and the men, for the most part, completed the remaining distance in their rubber boots, or got wet, or imposed upon the back and good nature of some accommodating person.

From Chapter 2: The Hybrid City of Nome

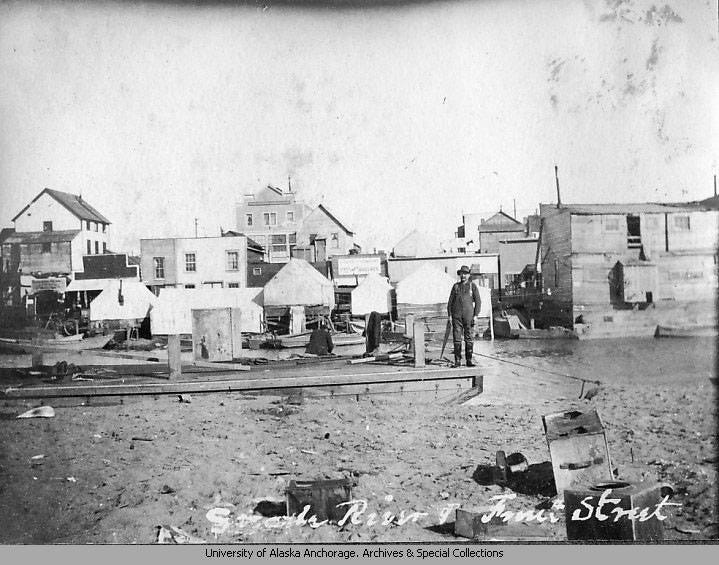

The town forms dense right at the shore, extending back and along upon damp and muddy soil hitherto covered by the deep and marshy moss. The Snake River, a sluggish, unnavigable stream, coming from the back-lying hills and through the tundra, empties into the sea where the town tapers off at the north, and thereby forms a sand-spit.

The first impressions after landing were those of confusion, waste, and filth. The shore was an indescribable mass of machinery, lumber, and freight of all kinds, the greater part of which represented fortunes thrown away. Scattered about and along the shore, looking for an opportunity to steal, were as tough a looking lot of rascals as one could meet. Upon walking into the center of the town one was greeted by a sight which beggars description. Certainly it was a case of "whited sepulcher." The whiteness viewed from afar disappeared. The main street was lined with hastily-erected two-story frame buildings, with here and there a tent— a series of saloons, gambling-places, and dance-halls, restaurants, steamship agencies, various kinds of stores, and lawyers' "offices." It was filled with a mass of promiscuous humanity. Loads of stuff drawn by horses and dog-teams were being carted through the narrow, crowded ways, and the cry of encouragement to the dogs of "Mush on" (dog French for Marchons) was heard frequently. Miners with heavy packs on their backs were starting out for the claims on the creeks and into the unknown interior, but the "bar-room" miner was far more in evidence.

It was not the typical mining camp where the population for the greater part is composed of hardy, honest people who have undergone privation to reach their destination, and thereby represent, in a measure, the survival of the fittest; for this was a great impossible hybrid sort of city, accessible by steamer direct from San Francisco and Seattle, where the riffraff and criminals of the country were dumped, remote from the restraints of law and order. I heard old-timers who had visited all the principal mining camps in recent years remark that this Nome was the "toughest proposition" they had ever encountered, and I must admit that it would be difficult to picture anything tougher. However, it was soon realized that the matter to be reckoned with was that of sanitary conditions, or rather the lack of them. The general "toughness" of things and the inconveniences of getting settled had been in the main foreseen and discounted, but the rather alarming outbreak of smallpox in the camp, and the reported filling up of the "pest-house," made matters somewhat more involved and complicated. There had been a warning in Seattle that certain vessels were bringing up persons infected with the disease, and two of the suspected ships were then being held in quarantine by the vigilant government representative, Lieutenant Jarvis, but the disease had, nevertheless, secured a foothold in the camp. Undoubtedly, however, the matter was grossly exaggerated, and there were probably more deaths from pneumonia than from any other disease. The smallpox scare, nevertheless, gave the doctors a good opening, for vaccination was strictly in order. Considering in retrospect the site of the place, the total absence of any sewerage, and the great motley crowd there herded together, Nome proved to be a remarkably healthy camp—a fact due, in the main, to the prompt measures for sanitation taken by General Randall immediately upon his arrival, and the introduction into the town, later in the season, of good water conveyed by pipes from the streams beyond. During the preceding year typhoid had been very prevalent and deaths numerous. A repetition was thus happily avoided, though, during the first days the prospects seemed indeed dismal, and the old-timers (always spoken of as "sour doughs" in Alaska) predicted that, after the rains should set in, the people were going to die like flies; and, without the least exaggeration, it certainly looked that way. I believe, nevertheless, that if the story could be told, it would be learned that more lives have been lost in that country through drowning than in any other way. Hundreds of gold-hunters, in small and unseaworthy boats, as soon as they could do so, left Nome to prospect the remoter coast and possible creeks, many of whom perished in the sudden and fierce storms which occur in the Bering Sea, and wives and mothers wondered why no letters came from Alaska.

Westward along the beach, for miles, all kinds of contrivances, from the simple hand-"rocker" to complicated machinery, were being used to get the gold; but the men did not seem cheerful in their work, and most of them would freely and candidly admit that they were not making even good wages. Among the many strange sights on the beach was an enormous machine, built upon huge barrels, which some of our friends with the blue-prints were making ready to dredge gold from the sea. It represented a great deal of money. When subsequently launched, and tons of sand had been taken by it from beneath the sea, not five cents' worth of gold was found to compensate for the enormous expense and labor. Not far away, at a point which was to be its terminal, men were landing as best they could the machinery, rails, and ties for the railroad of the Wild Goose Company, which was to extend for several miles back over the tundra to the rich placer-mines on the creeks.

Hundreds were living in tents upon the beach, thanks to the clemency of the weather. Within a very short distance from our camp, with their freight piled about, were the "syndicate," and quite unenthusiastic. There was defection in their camp. Actually, the "syndicate" were selling out, and without a struggle. Several of its members very soon bade us farewell, and pulled out for what they thought the "real thing"—quartz-mines in Oregon. And yet some of the mines on Anvil Creek even then, and with only a few men shoveling the pay dirt into the sluice-boxes, were turning out from ten to fifteen thousand dollars a day. To be sure, this was for the very few only, but, at the same time, it went to prove that the country was not a fraud. Even the dirt in those miserable Nome streets contained "colors," or small particles of gold; and it is an incongruous thought that, of all the cities of the world, Nome City, as it is called, most nearly approaches the apocalyptic condition of having its streets paved with gold!

We daily crossed the Snake River on "Gieger's Bridge" when going into the town for investigation and information. Gieger was an enterprising fellow who had built a rough but sufficiently substantial bridge at the mouth of the stream, and, by exacting a toll, he was making a pretty good thing out of it. Frame buildings of the wood of Puget Sound were going up like mushrooms throughout the town, and the noise of saw and hammer denoted that the carpenters were making small fortunes. "Offices" which could scarcely hold more than a chair and a table were for rent at one hundred to one hundred and fifty dollars a month, and these, too, frequently were merely spaces penned off in connection with stores or bar-rooms. Absurd prices were demanded for town lots of very uncertain title. I know of one instance where four thousand dollars was given for a lot on the main street.

The saloon which bore the proud sign “The Only Second-Class Saloon in Alaska” seemed to be the best appointed and to be playing to the largest audiences; but it was then too early for the miners to come in with their gold dust, and the gamblers, therefore, were not doing a harvest business. A man I had known at college was doing business in a tent pending the building of a bank with safe-deposit vaults, of which he was the general manager. Another, with whom I had attended law school, and whom I had never seen or thought of since, had come to Nome in the first rush from Seattle, and now, situated in Easy Street, was one of the leaders of the Nome bar.

The place was really under martial law. The town government, useless and corrupt, was practically nil; and as it was believed that the federal judge, with his staff of assistants, would not arrive until August, it was the plain duty of the military to preserve order and, so far as possible, leave legal matters in statu quo until the advent of the civil authorities as provided by the laws which had been recently enacted for Alaska.

For various reasons which seemed good and sufficient, we decided to quit Nome and go to Council City. We knew that Mr. Lane's company had large interests in that region—that he believed in it; and we knew people on the Lane who had gone thither direct on reaching Nome. It was said, too, to be a healthful country, with plenty of good water and even a belt of timber. One did not hear it much discussed at Nome—people did not seem to know much about it,—but what was said was favorable. As to the means of reaching it, information was scanty, and that somewhat discouraging, but certainly the thing to do was to go by boat east about seventy-five miles to the mouth of Golovin Bay, from which point we should have to travel up shallow rivers some fifty or sixty miles to Council City. C——, who had been a pretty sick man, but who had declined to follow certain "sound advice" and return home (having joined us from the Lane), and G——, another fellow-passenger, thought the move a good one, and agreed to come with us. We four, therefore, making selections from our respective supplies, sold or otherwise disposed of provisions which were less essential, for the carrying of freight and supplies in that impossible country, however short the actual distance, is a very serious and expensive matter.

A tent labeled "Undertaker," with the American flag on top, had just been put up for business across the way from us; and it seemed fitting that we should celebrate the Fourth of July by leaving Nome. This was accomplished on the little steamer Dora, belonging to the Alaska Commercial Company, not much to look at, but it afforded the greatest comfort and luxury we had known since the days at San Francisco, and, furthermore, it carried drinkable water. •~•

Alaska Steamship Company’s steamer DORA, circa 1912

This is an excerpt from Alaska and The Klondike: Early Writings and Historic Photographs, an anthology of selected writings by early explorers and travelers in Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada. Compiled and edited by Helen Hegener and published by Northern Light Media in 2018.